When Maureen C. Miller, Elizabeth and J. Richardson Dilworth Member (2021) in the School of Historical Studies, was completing her dissertation in the late 1980s, she found herself rather lonely, knowing not a soul in the diocese of Verona, Italy, where she was based for her research. In need of an activity to satisfy her curiosity and fill her free time when the archives and libraries were closed, she started to explore the churches in Verona and its countryside—of which there were surprisingly many, considering that medieval churches are often built of an ephemeral material: wood.

What became clear to her, as she explored, was the ways in which the physical evidence of the churches themselves often yielded a different—much earlier—foundation date than those she had found in her textual sources. Curiosity piqued, she began to build a database of all the churches in the area, searching more concertedly for the material evidence needed to make it more accurate. And so, despite her initial intentions to only use textual sources for her doctoral research, Miller followed her interests into the world of physical objects.

The humanities are replete with the study of objects—their history and significance have long been examined through varied disciplinary lenses. But, in the 1990s, right alongside Miller’s venture in Verona, developments within anthropology, archaeology, history, and art history had streamed together to produce the vibrant interdisciplinary field of material culture studies.

Material culture studies takes as its task the investigation of the relationship between objects and people. Where art history is interested in (often high-end) objects themselves—for example, comparing their forms and styles across time—material culture studies seek to engage (both high-end and everyday) objects as sources for human actions and ideas—for example, using a shift in style to investigate the human ideas or practices that drove such a change.

A key innovator in this infant discipline, who played a noteworthy role in nurturing and developing it within the realm of Medieval studies, was Caroline Walker Bynum, Professor Emerita in the Institute’s School of Historical Studies. Bynum’s significant—even field-shaping—impact on historical scholarship was celebrated earlier this year with a symposium published in the journal Common Knowledge. Miller, whose continued work in the world of objects has been much influenced by Bynum, spent some of her time at the Institute revisiting Bynum’s work to contribute to the symposium.

By the 1990s, Bynum had already distinguished herself with groundbreaking work on textual sources for religious life in the twelfth to fifteenth centuries C.E. “How strange,” but what a “wonder” it was that she turned her hand to this emerging discipline of material culture studies, noted Miller in her essay. “It was neither obvious nor inevitable that she would cap her extraordinary career by illuminating Christian devotional objects,” she continued.

A key characteristic defining Bynum’s scholarship, Miller says, is a meticulous process of revisiting her subjects, be they texts, objects, or artworks—something quite unique in an academic culture which encourages scholars to leap from one topic to another in an effort to demonstrate productivity. Miller focuses her essay on one particular object that Bynum revisited several times, a fifteenth century “beguine” cradle that originally held an effigy of the baby Jesus, now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Through detailing Bynum’s investigations of this cradle over several revisitations, Miller shows how her initial approaches involve a skillful deployment of the object as an illustration of arguments originating primarily from textual sources. Miller then goes on to highlight how, in later studies of the cradle, Bynum’s focus is the object itself, as she investigates how and why it works as it does. Miller describes the cradle as having agency of its own, or as possessing the key quality of “insistence,” in that it demands certain actions from the people that interact with it.

This fall, Miller worked with The Institute Letter to chart Bynum’s scholarship in material culture studies even more broadly, through the lens of a few Medieval objects that she regularly revisited throughout her career. In addition to the cradle, the Letter explores Bynum’s work on a wooden “retable,” a painted wooden panel which depicts the Virgin Mary emptying sacks of wheat into a funnel, from which both the baby Jesus and pieces of bread emerge, and a “pietà,” meaning “pity” or “compassion” in Italian, a sculpture that depicts Mary holding the body of Jesus after his crucifixion. The impact of Bynum’s return to all three objects is profound. The objects are transformed from background characters in a textual-focused narrative to central, influential players that perform a formative role in Medieval Christian piety.

The legacies of Bynum’s work, described by Miller in her symposium contribution, function as a series of invitations. The way Bynum centers objects and investigates them in later works invites readers to embrace wonder, beyond a “passive form of bedazzlement.” Asking questions of the objects engages an active form of wonder. It also inspires readers to have confidence in their own curiosity, as Bynum did: Miller asserts, “She teaches us again and again about the self-confidence that it takes to ask ‘How?’ and ‘Why?’.”

Finally, with her practice of revisiting sources, Bynum’s work encourages readers to take pleasure in returning to past work, be it questions or sources, to see what new insights arise. “The consolation I find in my recent immersion in Bynum’s rich oeuvre,” Miller concludes, “is that there is so much to be gained from resisting the pressures to rush on to the next thing and, instead, choosing to spend a little more time with sources that we know and love. In her honor, return to an object or text that you have enjoyed and afford yourself the pleasure of meeting an old friend and finding out something new.”

The Mystical Mill

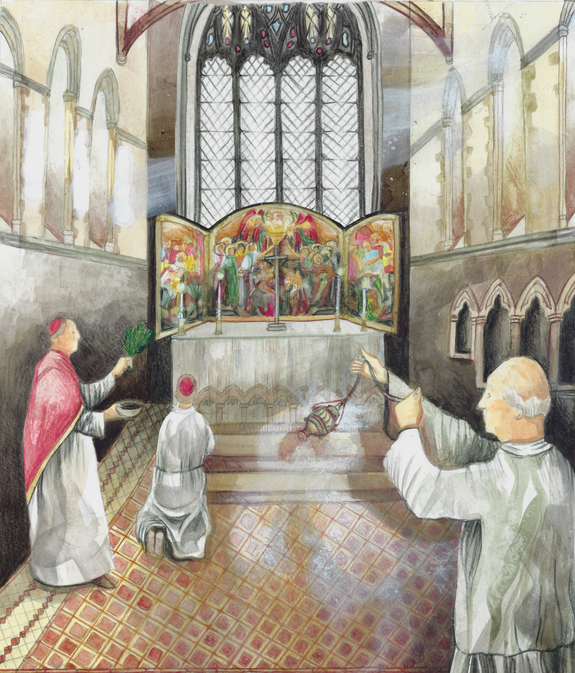

The wooden retable, dated to around 1440, is referred to by Bynum as a “Mystical Mill” or a “Host Mill.”1 She first introduces the object in her book Holy Feast and Holy Fast (1987), which examines the importance of food for religious women in the Middle Ages. The section in which the Mystical Mill appears is focused on the Eucharist, a Christian ritual commemoration of Jesus’s Last Supper with his disciples, where he instituted the practice of sharing bread and wine. Through a process known as transubstantiation, Catholics believe that the bread and the wine taken during the Eucharist literally transform into the body and blood of Christ. In Bynum’s words: “Christ had said it was human life, was body and blood.”

By 200 C.E., recreating this ritual had become a central practice in the church. But, by the late thirteenth century, there was a gradual restriction of the congregants who were allowed to receive the Eucharist. Eventually, only the priest received the bread (also known as the “host”) and wine on behalf of his flock. The withdrawal of the ability to receive the Eucharist further elevated its status—so much so that textual sources attest to congregants entering what Bynum calls a “spiritually and psychologically heightened state,” experiencing visions of Christ, after simply gazing upon the bread and wine. Simply put, at this time there was an enhanced sense that the bread and wine were God himself. Having highlighted this idea of God as food through surviving texts, Bynum goes on to make the point that this same notion began to pervade Christian iconography at this time. The Mystical Mill is cited as an example. The object evokes the amplified association between God and food seen in the texts, since, in Bynum’s words, “both Christ child and the host” emerge from the milled grain.

In Christian Materiality (2011), Bynum’s examination of how late Medieval Christians engaged with miraculous material objects, the Mystical Mill is itself the focus. Bynum first introduces it as part of a discussion of what she describes as “often quite expressionist and bizarre” Medieval iconography that was later “attacked,” sometimes physically, by Protestant reformers. She describes the Mill as “bold,” almost to the extent of being “religiously perverse.” Illuminating the “strangeness of medieval Christianity” in this way is “a recurrent, and important, theme in Bynum’s work,” states Miller. Bynum then goes on to outline how such images function in both “materializing” (i.e., making God’s presence physically manifest or tangible in the material world) and “somatizing” (i.e., embodying or expressing God’s nature in a corporeal form) ways. In the Mystical Mill, and other examples that Bynum cites, “body and material thing…seem to fuse or become each other.” Here, the Mill serves to emphasize what Bynum describes as the “extravagant” physicality of Medieval art. The sense that a reader gains from this discussion is that such images were not merely decorative but operated on multiple levels, including the theological, material, and symbolic.

The Fritzlar Pietà

We see a similar pattern in Bynum’s analysis of a second object to which she repeatedly returns: a linden wood “pietà” from Fritzlar, a small town in central Germany, which was probably made before 1350.2

Bynum analyzes the piece in Wonderful Blood (2007), a book which explores how Christ’s blood came to be the center of devotional practices and theological discourses between 1300–1500 C.E. In her discussion, she calls attention to the fact that the pietà, in its Medieval form, “actually had blood drops of papier-mâché affixed to the body.” For Bynum, “the discreteness of those elements,” namely the fact that the blood was rendered in individual drops, was significant. She linked them to a late Medieval “obsession” with quantification that again emerges through texts. Her textual evidence includes a story used by late Medieval preachers where the number of drops of blood was important: “a dying monk, seeing in a vision devils and angels weighing his deeds, begs for one drop of sanguis Christi [the blood of Christ] to be added on the scales on the side of his virtues in order to effect his salvation.” “Virtues, merits, and credits toward salvation,” could be, in her words, “counted off” in the same way as blood drops on pieces like the pietà could be enumerated.

When Bynum returns to the Fritzlar pietà in Christian Materiality, the object itself emerges triumphant. She uses the pietà to indicate that the distinction between an object being something and representing it in image form “was far from clear” in the Medieval period; some devotional objects, such as sculptures of Christ, were thought to actually be Christ in what Bynum calls “a special sense.” They functioned in a similar way to the manner in which the bread and wine of the Eucharist were thought to be Christ’s body and blood. Some objects achieved this status because they contained relics—the Fritzlar pietà is one such item. In Bynum’s words, “the graphically rendered side wound,” where today we see two holes, would have originally had a small shrine or container attached which housed a relic, such as a piece of holy bone said to be from the body of Jesus.3 When a relic physically touched or became embedded within another object, the significance of that object changed: materials that had been touched to holy relics were thought to become that with which they had made contact. As a result, when viewing the Fritzlar pietà, she argues that the Christian viewer would have responded both to the depiction of blood from Jesus’s body and the holy relic, which elevated the sculpture to the status of actually being Jesus’s body. The object and the thing they represented “were conflated, with no sense of incongruity.” In this analysis, the pietà is by no means an illustration—the power it would have held in its own right for a Christian believer shines through in Bynum’s writing.

The Beguine Cradle

The final object, the “beguine” cradle, is so-called because it hails from the Grand Béguinage of Louvain, Belgium, a religious community established for lay women in the twelfth century C.E.4 The object itself dates to the fifteenth century and is made from polychromed and gilded wood.

In Fragmentation and Redemption (1992), the object appears in Bynum’s discussion of the deep connections between Medieval women’s spirituality and their societal roles. She argues that the expectation that women would produce, nurture, and care for children influenced how women experienced visions of themselves bathing and nursing the infant Jesus, a trend that she identifies in the textual sources. In her Common Knowledge essay, Miller describes how, in this case, objects such as the beguine cradle “cluster in the chapter’s sections detailing the institutional, social, and intellectual contexts that answer the question ‘Why is this so?’”

By contrast, in Christian Materiality, the cradle appears not as an answer to an external question but as something that provokes many different questions and responses in its own right. In this publication, the object’s own agency, or “insistence,” is the focus. Bynum evokes how the beguine cradle, with its striking emptiness, powerfully calls out for activity and engagement. The absence of the baby Jesus creates a void that invites the viewer to respond: perhaps by placing the figure back in the cradle. This is the most obvious response that the cradle might insist upon, but, as Miller points out, Bynum emphasizes that it is merely one possibility. The cradle’s emptiness, Bynum goes on to argue, could be interpreted as a metaphor for the soul awaiting divine presence, inviting believers to contemplate what it means to welcome Christ into their hearts. In this instance, the beguine cradle appears in Bynum’s scholarship as an object with the agency to open numerous avenues for piety. In her words, it encourages believers to not only “see” the physical object in front of them, but also to “see beyond,” encouraging a spiritual experience and deepening their connection to God.

Maureen C. Miller is the Jane K. Sather Distinguished Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley. She was the Elizabeth and J. Richardson Dilworth Member (2021) in the School of Historical Studies. The author of three award-winning monographs on medieval ecclesiastical history and culture, her work has focused primarily on Italy and on the material culture of the secular clergy. She is presently researching the role of the church and its institutions in processes of documentary innovation.

[1] The object measures 137cm x 156cm. Today, it can be found at the Ulmer Museum, Germany (Inv.-Nr. AV 2150).

[2] The sculpture stands at just under 5 feet in height. Today, it remains on display within a baptismal chapel in Fritzlar’s cathedral tower.

[3] However, she declared it “impossible to tell” what this relic might have been.

[4] The object measures 35.4cm x 28.9cm x 18.4cm. Today, it can be found within the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Inv.-Nr. 1974.121a–d).