Security Versus Civil Liberties and Human Rights

The security of a nation and the safety of its population versus the protection of constitutional liberties and human rights is a quandary that arose in the aftermath of 9/11, but it is not novel to the twenty-first century. Discrimination between citizens and aliens, ethnicization of citizenship, the use of emergency powers in order to deal with the enemy and bypass the constitution, and the tendency to shift guilt and responsibility from the individual to a collective category (e.g., the Jews, the Muslims, etc.) are practices rooted in the past.

In my research, I have been looking at how governments and armies during World War I began to deal with these issues. The governments of almost all the nations that took part in World War I issued decrees and implemented measures against civilians of enemy nationalities who at the outbreak of the war were within their territory. Persons with ties to an enemy country were presumed to be more loyal to their origins than to the countries in which they worked and lived. German and Austro-Hungarian subjects living in France, Britain, or Russia, and later in all the countries that joined the Allies, and British, French, and Russian citizens who lived in Germany or in the Habsburg Empire, and then in Turkey or Bulgaria, were recast as dangerous, sometimes extremely dangerous, internal enemies.

Individuals with connections to enemy countries were in some cases passing through as tourists, students, or seasonal workers, but in most cases, they had been residents of the country for many years. Some of them were born in the country, some had married a national, others had acquired nationality papers, others were in the process of getting them. Many owned houses, land, or firms and spoke the local language. The outbreak of the war transformed them––independently of their personal story, feelings, ideas, and sense of belonging––into enemy aliens, accused of posing a threat to national security and the survival of each country.

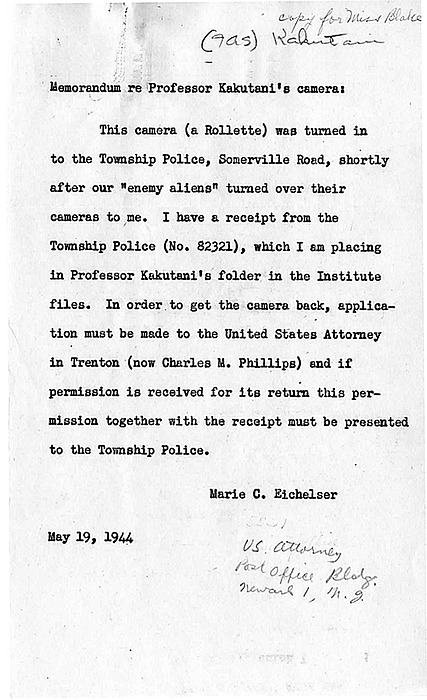

During World War I, government leaders (and sometimes armies) assumed full legislative powers and issued orders in council or decrees that limited personal freedom; restricted civil and political liberties; and eventually curbed the economic activities of the civilians of enemy nationality and jeopardized their property rights. Enemy civilians were required to register; abandon their homes in order to live in designated areas; not own cars, bicycles, and other means of transport or communication, like carrier pigeons or telegraphs; and submit to curfews. Each country adopted a combination of expulsion, repatriation, displacement, and, above all, internment of enemy nationals. Concentration camps opened almost everywhere, in Europe, in the United States, in Brazil, in the Dominions of the British Empire, and in the colonies.

Enemy aliens were prohibited from taking part in assemblies and demonstrations, owning newspapers and magazines or writing for them, and meeting in ethnic clubs and societies. In many countries ethnic presses were closed down, and the teaching of enemy foreign languages in schools was suspended. Many, trying to elude the severity of the restrictions, changed their surnames and hid their origins. Even music composed by musicians originating from enemy countries could not be played, and concert halls and opera houses had to switch to a different repertoire.

Almost all the countries at war issued a “trading with the enemy act,” which prevented enemy aliens from continuing their business activities. These acts ordered the seizure, confiscation, and sometimes the liquidation of patrimonies, shops, firms, shares and assets, patents, and copyright.

Passports and nationality papers proved to be less powerful than origins in defining national identity. Denaturalization (and consequently disenfranchisement) emerged as a common practice in France, Britain, Germany, and Canada, while a ban on new naturalizations was established almost everywhere.

As the war went on, the campaign against enemy aliens extended well beyond individuals who had originated from an enemy country. The loyalty of groups of citizens was questioned based on ethnic origin, religious belief, or former nationality. Among those affected were people who had recently acquired nationality papers (for example, the Ruthenians of the Habsburg Empire who had migrated to Canada or Germans in France who very recently had acquired citizenship); women who had lost their original citizenship and acquired a new one by the way of a marriage; minorities who had national aspirations (the Armenians or the Greeks in the Ottoman Empire, the Poles, Czechs, Italians, etc., in the Austro-Hungarian Empire); minorities who were resilient to forced nationalization and had long been discriminated against (the Jews almost everywhere; the Muslims in the Russian Empire); and minorities living in border regions whose loyalty was considered difficult to ascertain (the Alsatians and Lorrainians in France, the Italians of Trentino, South Tyrol, and Istria, etc.).

Popular reaction to the government policies took many forms: complaints, informing, reporting, acts of vandalism against properties occupied by enemy aliens (shop-window smashing, the pillaging and burning of shops and houses belonging to alleged enemy aliens), verbal violence, the hunting and lynching of supposed spies and enemies on the streets or fits of public and collective hysteria. The press fueled the anti-alien feelings with articles, cartoons, pamphlets, and campaigns of racial hatred. Pacifist and liberal groups almost everywhere had difficulties voicing their opposition to such behavior.

During the Great War, juridical measures, internment, violence, and anti-alien behavior contributed to the destruction or dispersal of many ethnic groups, altering the ethnic, social, and linguistic composition of many cities and regions in Europe and elsewhere. The campaign against enemy aliens also promoted a nationalization of economies, both by expelling foreign capital and presence and by increasing state control, thus laying the framework for developments in the decades that followed. The obsession for security justified violence and violations of international law, while resorting to the use of collective category prevented for many decades the emergence of a language and practice of human rights.