Building Archives of a Mobile Scholar Community

The Institute and its scholarship has a profound global reach, stretching well beyond the confines of its New Jersey campus. Yet this international scope also presents a challenge for archivists. Institute history is difficult to contain: records of scholars’ work proves as itinerant as the scholars themselves. Pivotal correspondence, documentation, and scholarship written on Institute letterhead (or increasingly from ‘@ias.edu e-mail addresses) continually pop up in new and unusual places. Part of the Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center's role is to consider if and when materials existing outside the Institute’s immediate space should be incorporated into the collection.

A challenge of precisely this nature arose earlier this year, when an archival collection surfaced that contained materials related to two prominent IAS scholars: Max von Laue, Member in the School of Math/Natural Sciences (1935, 1948) and Hideki Yukawa, Member (1948–49) in the same School. The archival materials do not come from a collection accumulated by either Member, but are instead documents received and collected by Friedrich Adolf Paneth (1887–1958), an Austrian-born chemist with no direct IAS affiliation but close contact with the community of IAS scholars. Paneth’s archive is wide-reaching. It documents a community of scientists and intellectuals allied against the development of atomic weaponry, providing insight into vital contributions made by IAS scholars in this realm.

Paneth was born to Jewish parents and educated in Vienna. After gaining his Ph.D. in organic chemistry, he went on to study radioactivity and particularly radiochemistry. After stints in Scotland, England, and the Czech Republic, Paneth held more permanent positions at a series of German universities from 1919–1933, including in Hamburg and Berlin. However, while on a lecture tour in 1933, Paneth learned that Hitler had seized control of Germany and made the decision not to return. Like many other scholars of the time, Paneth would become a scholar forced into exile from the country where he had seen the greatest success in his career and, following the occupation of Austria in 1938, from his native country as well.

In 1938, the University of London appointed Paneth a Reader in Atomic Chemistry and, by 1939, he became a Professor of Chemistry and Director of the Laboratories at the University of Durham. In 1943, he was appointed the head of a joint British-Canadian Atomic Energy team which specialized in chemistry, and moved to Montreal for the duration of the war. At the end of the war, Paneth returned to Durham where he remained until his retirement in 1953, at which point he accepted a prestigious opportunity as the Director of the Max-Planck Institut für Chemie in Mainz. Paneth remained in the position until 1957, when he became famous in the scientific community for his role as a signatory on what is today remembered as the “Göttingen Manifesto.”

The Göttingen Manifesto is a declaration published on April 12, 1957 by Paneth and seventeen other noted scientists, warning against arming the West German government with tactical nuclear weapons. Significantly, as we might expect given the Institute’s commitments to the freedom of expression for academics, the manifesto featured several IAS scholars as signatories, including von Laue and Yukawa.

The Paneth collection documents the exchanges between scholars that took place in the wake of his involvement in the manifesto. It comprises 82 folders of original documents, correspondence, offprints, and printed ephemera, as well as appeals and newsletters from the Japan Council Against A & H-Bombs, including a two-page speech by Yukawa entitled “Nuclear Testing is Everybody’s Business.”

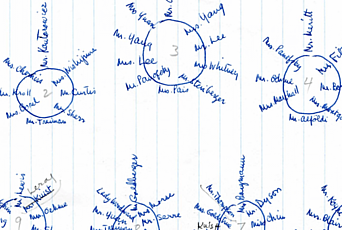

As one of the original signatories on the manifesto, Paneth—already imbricated in politics because of his efforts in the war—would also become a part of a much different history of scholarship that worked independently of, and in this case, in open opposition to state policy. As well as tying him to his co-signatories, von Laue and Yukawa, Paneth’s signature linked him to a host of scholars that we celebrate today on this campus, including J. Robert Oppenheimer, Albert Einstein, J. Ernest Wilkins, and many others. Although never holding an IAS position himself, Paneth is inextricably connected to the history of the Institute through its scholars’ affiliation and affinity within a broader network.

The collection is a reminder of the inescapable politics of scholarship and, reciprocally, the significance of academic institutions like the Institute that create dedicated space for truly independent forms of inquiry. As a historical document, it attests to the international climate out of which the Institute for Advanced Study emerged in the 1930s, and it underscores the necessity of looking beyond immediate IAS scholar archives to piece together the history of a community defined by migration and mobility.