A Window into Early Twentieth-Century Arabic Manuscripts Transactions

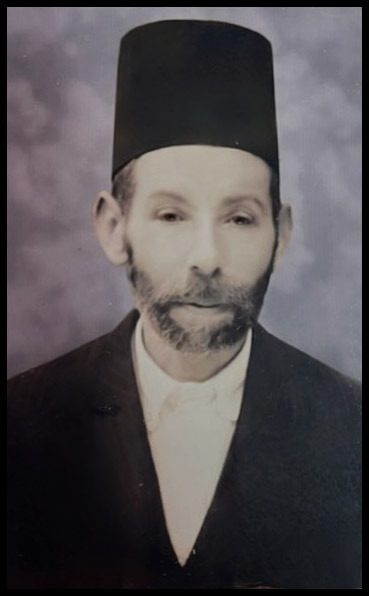

On Tuesday, September 17, 2024, a team of librarians from the American University in Cairo (AUC) arrived at the al-Khanji Bookstore in downtown Cairo to oversee the transfer of a rare archive documenting the al-Khanji family's role in the cultural life of the region for nearly a century. This transfer was the result of a cooperation between AUC and five North American academic institutions—the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ; Princeton University; New York University; the University of Michigan; and the College of Charleston—to purchase the archive, preserve it, and make it available to researchers. The al-Khanji archive consists of several thousand documents of various types produced by the well-known Syrian-Egyptian al-Khanji family of booksellers and publishers. Completely unique as the only known surviving archive of a manuscript seller in the region, the archive documents the book-selling and publishing business established by Muhammad Amin al-Khanji after immigrating to Cairo from Aleppo in the 1890s to the 1960s, when the business was run by his sons Sami Amin (d. 1966) and Najib (d. 1980). An exceptionally rich source, the archive promises to open numerous new lines of research into print history, manuscript studies, and Muslim and Orientalist intellectual networks in the first half of the twentieth century.

The archive contains particularly valuable material for Islamic manuscript studies and provenance history, filling in massive gaps in our knowledge of some of the most important repositories of Islamic manuscripts in the world. The early twentieth century witnessed a mass translocation of Islamic manuscripts that resulted in the formation of many of the most important collections in the world, now housed in the libraries of the Middle East, Europe, and North America. This translocation of manuscripts is poorly understood, and the provenance of the manuscripts that make up these collections is largely unknown. The al-Khanji family played a key role in this translocation, and the archive holds documents that tell important chapters of this story.

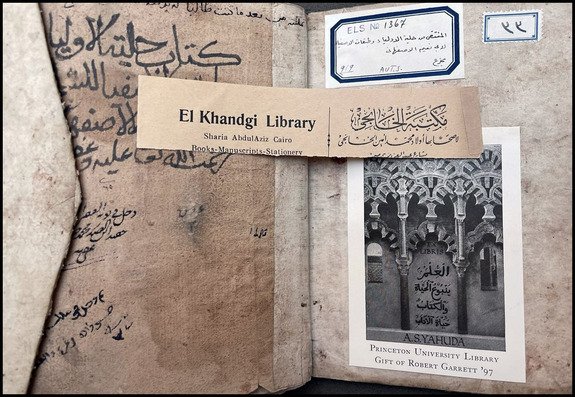

Garrett Davidson, George F. Kennan Member in the School of Historical Studies and one of the scholars who initiated the cooperation, first became interested in the al-Khanji booksellers when, in the summer of 2016, he surveyed some one thousand Arabic manuscripts held in the Princeton University Library, most of which were previously owned by the British Jerusalem-born orientalist and bookseller Abraham Shalom Yahuda (d. 1951). As he perused these manuscripts, he came across traces of their previous lives and wondered about the trajectories of these manuscripts to Princeton, New Jersey, which seemed an unlikely destination for Islamic manuscripts produced in the medieval and early modern Near East and North Africa. These clues to their provenance included notes penned by previous owners and readers, such as a note indicating that a manuscript was once endowed to the College of the Anatolians at al-Azhar University. Clues also came in the form of scraps of paper left between the leaves of some manuscripts as bookmarks. These scraps and bookmarks often provided only vague clues and glimpses of the manuscripts’ lives before arriving at Princeton. For example, a page of an Egyptian calendar from 1931 containing dates for the Hijri and Coptic calendars and a Cleopatra brand cigarette wrapper indicate that these manuscripts passed through Egypt at some point, but provide no specifics of provenance. However, in some cases, these ephemera comprised more explicit evidence. Most notably, he found several pieces of the business letterhead of the al-Khanji Bookstore, seemingly providing direct evidence of these manuscripts' exact provenance.

The following summer, in 2017, Davidson pursued this connection to al-Khanji further at the archive of Yahuda in the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem and discovered a file containing correspondence between al-Khanji and Yahuda. This correspondence confirmed that al-Khanji was a primary source for Yahuda’s manuscript library as well as the thousands of manuscripts he sold to collectors and libraries in Europe and North America. Because this file contained just a fraction of their overall correspondence, it provided only a partial view of their clearly extensive dealings in manuscripts. However, it did reveal that al-Khanji was sourcing manuscripts for Yahuda from all over the Middle East and North Africa, but it did not provide specifics. In the absence of further evidence, it seemed little more could be learned about this connection.

Then, in the fall of 2022, while Davidson and Rana Mikati, Visitor in the School of Historical Studies, were both on sabbatical in Cairo, they visited the al-Khanji bookstore, which is still at the address it was nearly a century earlier, when al-Khanji and Yahuda corresponded. At the shop, they met the founder's grandson, Muhammad Amin (b. 1946), who has run the business since 1973. Upon showing him images of his grandfather’s letterhead at Princeton and asking him if he knew of the connection, he rifled through his desk drawers and eventually produced a postcard Yahuda sent to his grandfather in February of 1932. Although the text of the postcard consisted of only a few lines, it significantly noted that al-Khanji was receiving monthly payments from Yahuda. Optimistic, Davidson and Mikati cautiously queried him about further documents; Mr. al-Khanji said he would look and that they should return.

Davidson and Mikati began making weekly visits to Mr. al-Khanji, during which he would produce a few more letters. After several months of meeting with Mr. al-Khanji and discussing the family’s role in the manuscript trade, he eventually gave them access to the entirety of his grandfather’s papers. Remarkably, most of these papers had been preserved by his uncle, Sami Amin, in a closet of the family bookstore, where they remained for decades before being discovered by Mr. al-Khanji in the 1990s.

After conducting a preliminary survey of this material, consisting of some two thousand letters and various other documents related to the al-Khanji family book business, it was clear to Davidson and Mikati that the archive constituted an unparalleled source on the world of Islamic manuscripts in the twentieth century. The letters detail the inner mechanics of their business and make it overwhelmingly clear that the al-Khanjis played a previously unknown but pivotal role in the translocation of tens of thousands of Arabic manuscripts and the formation of some of the most important manuscript collections of the twentieth century. The list of customers who emerged from the archive reads like a who’s who of twentieth-century manuscript collectors. His major customers include Ahmad Taymur Pasha (d. 1930), Ahmad Zaki Pasha (d. 1934), and Tal’at Bey (d. 1927), whose libraries together make up a large share of the Egyptian National Library’s manuscript holdings. Other important customers include the Egyptian Grand Mufti and Shaykh al-Azhar Muhammad Bakhit al-Muti’i (d. 1935), whose collection of 8,000 manuscripts is now part of al-Azhar University Library. The Egyptian National Library and Cairo University Library were also revealed to have been among their customers.

For Davidson and Mikati, one of the most fascinating materials in the archive are the letters exchanged between Muhammad Amin al-Khanji and his sons during his buying trips to Palestine, Syria, and Iraq. The letters provide a unique and intimate view of these trips and document the thousands of manuscripts he purchased and then sold to customers in Egypt, as well as to Yahuda, who then sold them to his customers in Europe and the U.S. Traces of these buying expeditions can be found on manuscripts at Princeton and the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin, Ireland, in the form of notes composed by al-Khanji indicating their places of origin and their assigned number in that series of manuscripts, for example, "Mosul 53."

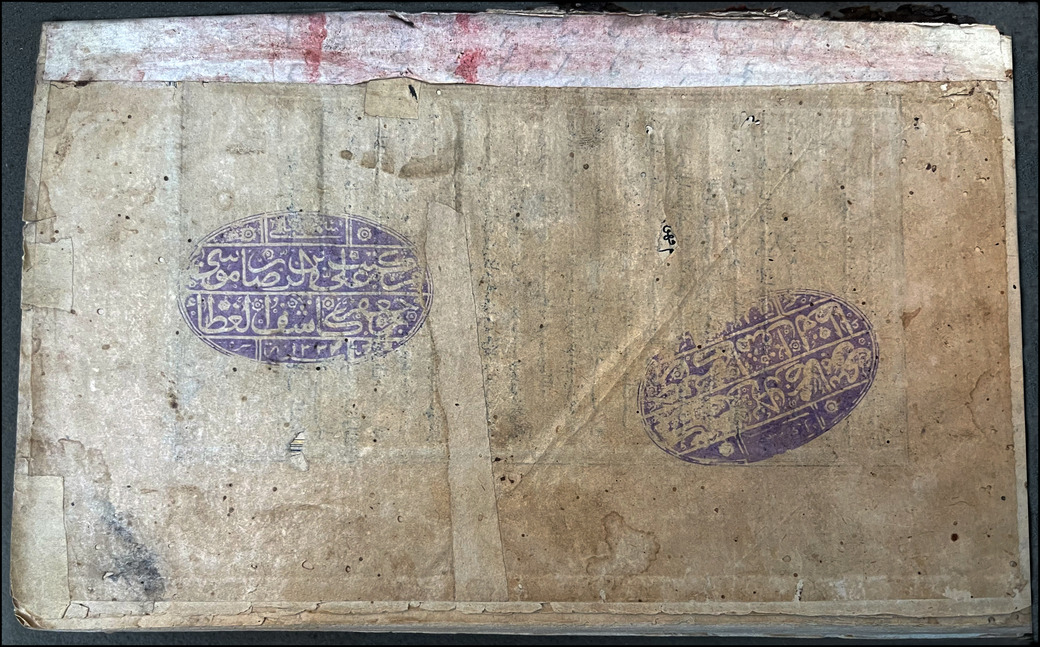

Another fascinating source in the archive is the journal al-Khanji kept on his 1930 buying expedition to Iraq, in which he recorded his daily activities and expenses for the nine months he spent traveling throughout the country. Through this, we can reconstruct the networks of Iraqi booksellers and collectors active at the time, from Najaf to Sulaymaniyah. In one case, al-Khanji records a list of manuscripts he purchased from the collections of members of the prominent Shi’ite Ulama family Kashif al-Ghita’. Based on these lists, we are able to trace some of these manuscripts to their current locations in Dublin and Princeton.

The archive is also rich in materials on the al-Khanjis as publishers and distributors of printed books in Cairo from different parts of the Arab and Islamic worlds. Among the important materials for the history of publishing in the region preserved by the archive is the considerable correspondence with the Iraqi publisher Maktabat al-Muthanna, whose offices and papers were destroyed during the U.S. invasion of Iraq, making what survives in this archive quite valuable.

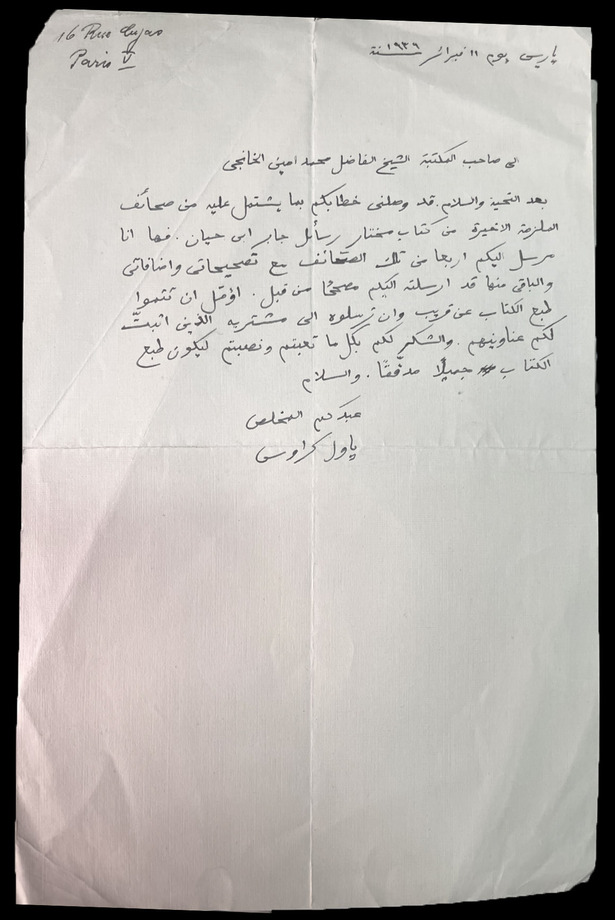

In addition, there is correspondence with European libraries showing the extent to which they purchased books published in Cairo through al-Khanji, with Western scholars who either published their editions of Arabic works with al-Khanji (e.g., Paul Kraus) or regularly purchased Arabic book publications for their own libraries or those of their colleagues (e.g., Paul Kraus purchasing books for Carl Brockelmann).

In March of 2023, Sabine Schmidtke, Professor in the School of Historical Studies, was in Cairo for research, met with Davidson and was intrigued by the al-Khanji find. She proposed the idea of a cooperation between institutions to preserve and study the collection. Al-Khanji, who was keen on the archive being preserved intact in Egypt was receptive to this idea, and Davidson and Mikati initiated discussions with AUC. Schmidtke then made the crucial first financial contribution to acquire it, with funding provided by the Gerard B. Lambert Foundation. Evyn Kropf of the University of Michigan Library and Guy Burak of New York University Library soon joined the cooperation. Upon learning of the cooperation, the late William Noel, Librarian for Special Collections at Princeton University Library, enthusiastically supported it and played a key role in making it a reality (prior to his untimely passing in April 2024). From AUC, Ahmad Khan and Lamia Eid worked creatively to bring this novel cooperation between six institutions to completion.

In addition to the material in the al-Khanji archive, the research will include archival material and data held in the archives of institutions and individuals with whom al-Khanji dealt, such as the British Library, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, the Leiden University Library, and others.

Al-Khanji not only dealt with manuscripts and books, but was also a prolific publisher. Davidson and Mikati have so far identified around 160 books published by him, and expect that many more will be found as research continues. In addition to an inventory of al-Khanji's publications, an analysis of the entire corpus and the occasional prefaces he added to each book will help to better understand his principles in selecting titles and preparing editions and prints of the books in question.

Another source of information on al-Khanji's editorial principles and selection of titles is his correspondence with colleagues and patrons, in which he occasionally comments on these matters, as well as the observations of others on his publishing activities. One of the most revealing examples of this latter category of source is the German Arabist and bibliophile Friedrich Kern's (1874–1921) comments on al-Khanji's publishing policy in a letter to Ignaz Goldziher, dated July 31, 1906:

Now that the archive has been acquired and transferred to the AUC library, the next steps for its scholarly study are being prepared. As a first step, the AUC will digitize the entire archive. A detailed inventory will then be prepared and itemized to enable the identification of specific lines of research. We plan to invite other scholars in the field to participate in the study of this rich material and hope to convene a first workshop on the al-Khanji archive at the Institute in autumn 2025.

Read more about the acquisition on The American University in Cairo website.