Rediscovering One of the Institute's First Women of Color

Since 1933, the Institute has welcomed over 8,000 Members comprising scholars from nearly every part of the globe. For many of these scholars, the Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center holds some of the only extant archival records documenting their life and work. The Archives Center answers hundreds of requests a year related to household names like Albert Einstein, T. S. Eliot, and J. Robert Oppenheimer; however, just as frequently, it receives requests for information regarding scholars with lesser-known histories. The Archives Center is often one of the few places where researchers can find the remaining traces of those scholars’ stories.

In the Spring 2023 edition of The Institute Letter, archivist Caitlin Rizzo outlined her research into Thayyoor K. Radha, one of the earliest women of color at the Institute. Radha joined the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences in 1965–66 as a Member, but her continued success was rendered virtually undiscoverable after her marriage to Vembu Gourishankar, a professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the University of Alberta, which saw her change her surname.

Shortly after publication in The Institute Letter, the Archives Center received a message from Radha’s daughter, Sita Gourishankar, noting her excitement at seeing her mother’s profile.1 Sita set up a meeting between her mother and Rizzo, allowing the archive to collect even more elements of her story. Some highlights from their conversation are shared below.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Archive: Tell us a little more about your early life and the family dynamics that helped influence the path you would eventually take.

Thayyoor: My parents, T. K. Krishna Iyer and C. V. Krishna (neé Kaveri), were both born in Kerala, in South India. In 1920, when they married, my father was 18 and my mother only 8 years old. This was, in fact, the result of an unfortunate situation. My mother’s mother had passed away and, as a young woman with no mother, she was particularly vulnerable. My father’s mother encouraged marriage as a way to take care of my mother.

I was the fourth of five children. My older brother excelled at chemical engineering and both of my older sisters did extraordinarily well in high school, but, in the 1940s and 1950s in Kerala, girls were not educated after high school and my sisters stayed home rather than continuing their schooling. They attended art classes as they waited for the opportunity to marry.

At the point I finished my early education, my sisters were still unmarried. Rather than have a third daughter waiting to marry, they encouraged my father and mother to allow me to continue my education. I attended an intermediate college for women and I performed extremely well (my marks were higher than both my father’s and my brother’s had been). I wanted to continue my education. Despite having my highest marks in mathematics, I wanted to pursue physics. The only school that would allow me to study physics was where my father had gone, the Presidency College in Madras. When I got there, his picture was still on the wall. My mother did not want me to go—she was scared for me to be amongst men in a co-educational facility. My father convinced her to let me go.

A: Can you discuss your time at the University of Madras?

T: When I finished [at the Presidency College], I received a gold medal for my work and had a choice of what to do next. At this time, Alladi Ramakrishnan, Member (1957–58) in the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences, had decided to start a course in theoretical physics at the University of Madras in Chennai. There were three other girls there at that time. We all knew of each other and were waiting for one another to join.

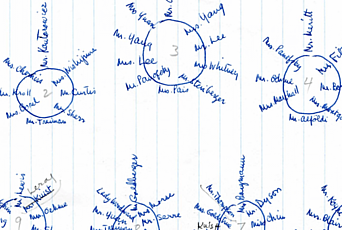

At this point, no one in Chennai had worked on particle physics at all. Ramakrishnan, however, had heard about the field and knew that it was exploding. He knew Homi Bhabha, who ran the Tata Institute in Bombay, and he was able to give us each a paper on particle physics. We spent three months learning about complex variables, of which we had no understanding beforehand. That’s how it started. Ramakrishnan had the idea to collect a bit of money from the students to put towards inviting professors visiting the Tata Institute to come from Bombay to Chennai for lectures. That was how we were able to meet so many scholars, including Robert Marshak, Member in the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences (1948); Leonard I. Schiff; and Donald Glaser.

Those visiting professors would bring pre-prints with them, which was transformational. Up until that point, we could only receive physical journals in India via sea mail. It would take three months for a paper to arrive. By the time you received a published paper, other scholars with access to pre-prints had already had months to work on problems. By the time we started our research, it would be obsolete. However, when scholars visited, we could talk with them directly. They gave us advice and listened to our ideas. Once we knew these professors, we could write to them and ask them to send us their pre-prints by air mail. Slowly, we could catch up.

Then, we started to write a lot of papers. Every week there was a new particle to discover. Everyone was jumping on problems because there were so many things to choose from. My thesis consisted of a set of fourteen published papers from this period, all related to particle physics, Feynman propagators, and particle interactions.

A: Tell us about your time at the Institute for Advanced Study. Did you collaborate with any notable Faculty or Members while you were here?

T: In June 1965, while at Chennai, I received a letter from J. Robert Oppenheimer inviting me to come to the Institute for Advanced Study from September 1965 to April 1966. The Institute was an extraordinary place. I walked the street where Albert Einstein lived. I had discussions with Sergio Piero Fubini (Member in the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences, 1965–66) nearly every day. I also saw Abraham Pais (Member in the School of Mathematics, 1946–50; Faculty in the School of Mathematics, 1950–63; and Member in the School of Natural Sciences, 1980–81), and, I believe, Julian Schwinger. I also interacted with Freeman Dyson (Member in the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences 1948–49, 1950; Faculty in the School of Natural Sciences, 1953–2020) and Oppenheimer himself while I was there.

I met with Oppenheimer privately. I had not received funds for my travel and I went to ask his secretary about the money, as I was not quite well off at the time and it made a big difference. I was surprised to find that Oppenheimer wrote back and told me that the money would be wired immediately. When I finally met him, I was struck by his interest and knowledge of the Bhagavad Gita. He asked me if I knew it. I said I had never learned it seriously enough to discuss. He had read the whole book in Sanskrit and he believed in it deeply. That’s how he went ahead with the atomic bomb—he said it guided him in his duty.

A: You met Vembu Gourishankar in Edmonton, where you were giving a seminar at the physics department of the University of Alberta. After you married and moved to Canada, what happened?

T: After my marriage I arrived in Edmonton too late in the year (1966) for the start of the academic term, but the University of Alberta asked me to instruct a course on Feynman quantum electrodynamics. In December, they offered me an assistant professorship, but, by that time, I was pregnant. There was no adequate child care then, and no day care. Smoking was not prohibited, and I could not find a babysitter who did not smoke. I decided that I would have to take a leave of absence to care for my child. I gave a seminar on June 7, and three weeks later my child was born. By September, I started going back to work whenever I could. I would spend the afternoons there reading to try to keep myself in touch with the field in the hopes that I could return. But then I had a difficult second pregnancy.

Eventually, I realized it was too much. I had missed three or four years of the latest research. I tried to go back and ask for my job once again. However, at that time, the university was having difficulties. Even men could not keep their jobs and the university felt they could not afford to hire women, especially women whose husbands were already provided for.

In 1973, I started taking computing courses at the university and, again, I was at the top of my class. The physics department immediately sought to hire me, as they needed a programmer who could do numerical analysis on the computer. I was one of the only ones that knew physics and programming, so I got the job immediately. I would do the work at home and send the results to the physicists on the computer. I used to give them ideas, so many of them listed me as a co-author on their work. There are even one or two articles that I wrote on my own. From 1976–92, I was a computer programmer.

I also started doing volunteer work at the blood donor clinic and the cancer institute. I found great satisfaction in helping. When I started working at a Good Samaritan nursing home, they suggested that I take a palliative care course. That was an important life experience for me; I learned how to take care of terminally ill people. Later, at the elementary school where my grandchildren were, I realized no one was teaching the children coding. The school said they didn’t have anyone who could teach them, so I learned and I taught them and the kids loved it. They all wanted to leave their classes to learn to code. The teachers recommended me for the YMCA Women of Distinction award. I was one of ten women nominated, and I won.

Although I could not pursue my research career in physics, I continued to tutor many university students in math and physics. I tried to keep up with the latest developments in particle physics. My advice to my children and grandchildren and all of the younger generations today is to pursue your passion, learn from others, and be humble. Your life will be enriched beyond your imagination.

We thank the Gourishankars for their willingness to fill the historical gaps in the archive.

1 Sita Gourishankar is a Physician and Professor of Medicine in the Division of Nephrology and Transplantation Immunology at the University of Alberta.