In August 2024, the Institute’s Historical Studies - Social Science Library (HS-SS) received a gift that sparked a host of new connections to be made between old and new titles in the library’s holdings.

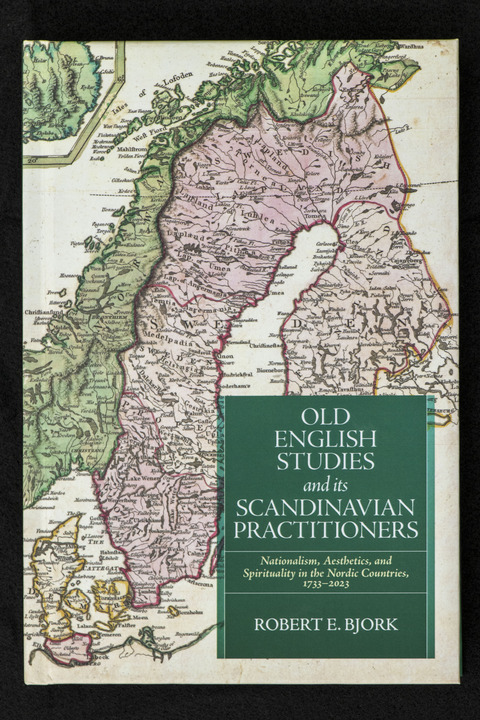

The gift was a copy of Old English Studies and its Scandinavian Practitioners: Nationalism, Aesthetics, and Spirituality in the Nordic Countries, 1733–2023, sent by its author Robert E. Bjork, who served as a Member (2004–05) in the School of Historical Studies. Bjork dedicated his IAS Membership to working on the book, and speaks of his “gratitude” to the Institute in the acknowledgements.

His subject is the study of Old English literature, a collection of works written in the earliest recorded form of the English language between approximately 650–1100 C.E., including, most famously, titles such as Beowulf. In his book, Bjork outlines how the study of Old English began around 200 years ago, not in England but in Scandinavia, spearheaded by Danish scholar N.F.S. Grundtvig (1783–1872).

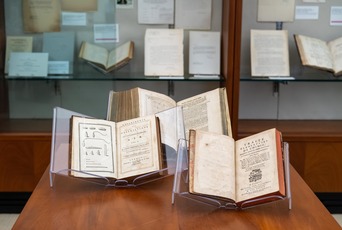

Upon receiving the book, Marcia Tucker, HS-SS Librarian, recalls, “It struck me that there was a set of books in the rare book room that might pair well with Bjork’s volume.” The Institute’s rare book room is home to around 3,000 titles. At the core of the collection are a number of first editions of significant works on the history of science, presented to IAS by Trustee and Trustee Emeritus Lessing J. Rosenwald (1940–79), but it has since expanded to cover diverse subject areas, including the Spinoza Research Collection and other titles in early modern history.

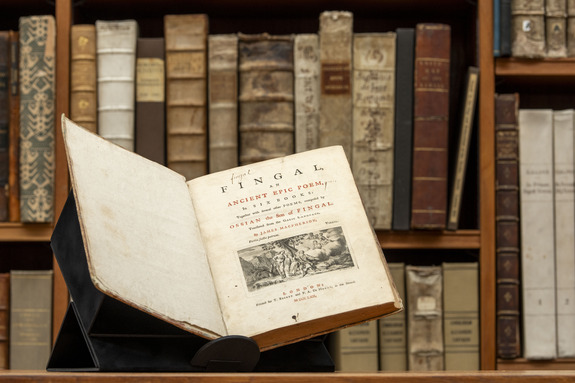

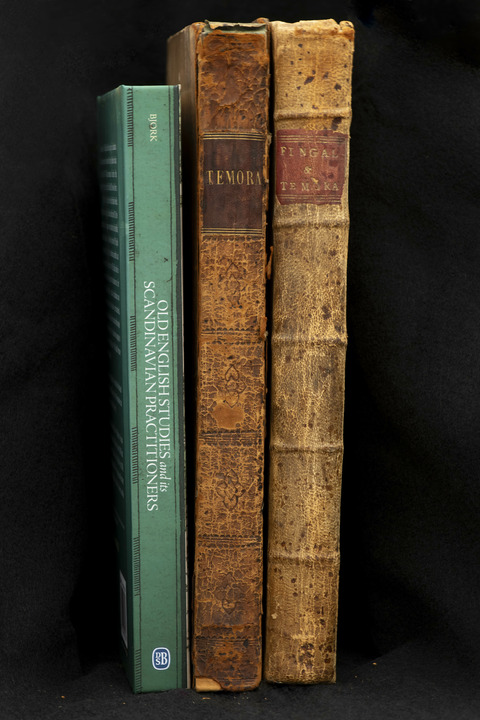

The particular titles from the Rosenwald Room that sprang to Tucker’s mind when she received Bjork’s book were both first editions: Fingal, An Ancient Epic, published by James Macpherson in 1761, and Temora, An Epic Poem, published by the same author two years later. Like Bjork’s book, these were presented to the Library by a former IAS scholar: Lionel Gossman, Visitor (1978–79, 1983, 1986–87) in the School of Historical Studies. But this was not the only common thread between the publications. They are linked, Tucker points out, by the theme of Romantic nationalism.

Romantic nationalism emerged as a powerful cultural and political force in Europe during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, entwining closely with the broader Romantic movement in arts and culture. This ideology viewed nations as organic entities, naturally arising from shared language, culture, history, and traditions. It developed in reaction to Enlightenment rationalism and the universalist ideals of the French Revolution, influenced by philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Gottfried Herder. It gained particular strength in Central and Eastern Europe, playing a significant role in movements for national unification or independence in countries like Germany, Italy, and various Balkan nations. Crucially, Romantic nationalism’s emphasis on developing and celebrating distinct national identities often saw its proponents looking to idealized versions of the past for inspiration.

It is this element of the Romantic nationalism movement that is exemplified in Macpherson’s texts. Fingal, An Ancient Epic and Temora, An Epic Poem purport to be authentic translations of ancient Gaelic manuscripts, which preserve poetry composed by the legendary Scottish bard Ossian. These epic poems recount the deeds of the hero Fingal and his son in a mythic Celtic past.

However, in reality, these works were largely of Macpherson’s own fabrication. His critics became suspicious almost immediately upon the publication of the first volume and the authenticity of the books was openly challenged. Eventually, their status as forgeries was confirmed: Macpherson, who was unable to produce the original manuscripts from which his so-called translations were made, had adapted elements from Celtic mythology, ballads, and folklore to invent the texts, while adjusting the Gaelic names so that they would be easier to read by an English audience. Despite their status as fabrications being exposed, Macpherson still succeeded in creating an idealized vision of Scotland’s past that appealed to contemporary Romantic nationalist tastes. His works sparked widespread interest and influenced Romantic writers and even musicians across Europe, from William Blake and Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Franz Schubert and Johannes Brahms.

Romantic nationalism is also an important springboard in Bjork’s book. Similar sentiments to those motivating Macpherson to craft his fraudulent epics likewise drove these early Scandinavian studies of Old English: Bjork describes Romantic nationalism as “a first mover” in Old English studies in the Nordic regions. Nationalistic fervor, he argues, arose in response to political turmoil among the countries of Scandinavia, as well as threats of Napoleonic invasion, leading Scandinavians to glorify their ancestral heritage and unique cultural identities. This manifested not only in new constitutions and political movements, but also in art, music, literature, and material culture celebrating Norse and Viking themes.

Nationalism, Bjork contends, is also partially responsible for the relatively obscure status of Scandinavian scholarship on Old English, despite the discipline originating in the region. The language barrier caused Scandinavian contributions to be overlooked, as did “the nationalistic bias in Old English studies,” which “has shifted [focus] decidedly away from Scandinavia (and Germany) to England and North America.”

Although Romantic nationalism provided an important initial impetus for the study of Old English in the Nordic countries, Bjork indicates that the driving force for continuing those studies has evolved over time. “The qualities Scandinavians now seek in Old English literature—that we all seek,” he writes, “are transnational, existential, spiritual, and human.” He emphasizes that these texts resonate with fundamental questions about the human experience, marking a shift away from viewing Old English literature as a historical artifact to appreciating its deeper insights and emotions that remain relevant today, extending far beyond national boundaries.

Placing these titles—both Bjork’s and Macpherson’s—side by side allows the reader to trace the evolution of Romantic nationalism’s influence on literary studies from its role in spurring the creation of idealized national epics to its impact on shaping academic disciplines, while also highlighting a recent shift towards a more universal appreciation of the origins of disciplines like Old English studies. The Historical Studies - Social Science library, with its varied collection of old and new works, provides the Institute community with bountiful opportunities for the making of such connections across boundaries and time.

Robert E. Bjork serves as Foundation Professor of English at Arizona State University, specializing in Old English and Old Norse language and literature. His latest book, Old English Studies and its Scandinavian Practitioners: Nationalism, Aesthetics, and Spirituality in the Nordic Countries, 1733–2023, will be translated into Russian for publication in 2026 and distributed to libraries and universities in Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, among others.