In his solo string works, Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach was renowned for a powerful paradoxical effect: namely creating the illusion that multiple instruments were playing in harmony when this was not the case. Bach’s technique, known as “implied polyphony,” often involved rapidly oscillating between two melodies in different octaves, infusing his music with an orchestral effect through the use of only a single violin or cello.

Paradoxes of a musical nature also abound in the work of Clara Latham, Martin L. and Sarah F. Leibowitz Member and Edward T. Cone Member in Music Studies in the School of Historical Studies. The contradictions that inspire her work surround the perceptions of musical labor, with particular reference to music technology. Broadly speaking, Latham is intrigued by the dualities in the perception of music as both a pastime, a source of fun and emotional fulfillment, and an activity that requires intense effort to perfect.

The association of music and leisure often causes the labor involved in acquiring musical skill to be overlooked. To explain this, Latham gives an example from her experiences in musical conservatory. In such settings, students spend up to 10 hours a day in a practice room, and yet, Latham tells us, “Friends and family will still urge them to get out their guitar in social settings, saying something like, ‘don’t you want to play for us?’” She contrasts this with attitudes to other enterprises such as cooking: “The same people who urge a musician to pick up their instrument would certainly think twice about saying to someone who owns a restaurant, ‘Oh, would you like to come and cater my party for free, just because you love cooking?’”

Because music is often perceived as a passion, something that a performer feels driven to do, there is a pervasive assumption that it does not count as work. Latham describes falling into this fallacy herself during her career as a musician: “When I was 20, before I went on my first tour, I had mental images of our band just rolling up on a bus and having all these people at the ready, setting up our stuff. In reality, it was me and 8 guys in 2 small rental cars driving 10 hours a day, sleeping on strangers’ couches. It was hard! Those experiences definitely inspire the question of ‘why do people always assume that music is not work?’”

While Latham was teaching the history and practice of electronic music at her home institution, The New School’s Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts in New York, she noticed in some of her students a belief or an expectation that technology would make them better musicians. “Some people think if they just have the right tools and the right technology, they will magically be rendered an expert DJ or musician,” Latham says with a smile. The sense gained from a conversation with Latham is that musical labor is at once unacknowledged and also something that musicians seek to do away with.

Latham’s personal confrontation of this paradox inspired her latest research efforts in the field of musical technology, which form the focus of her IAS Membership. Her project explores the early days of electronic music, the emergence of which coincided with a period when music began to be viewed as a commodity due to new recording technologies such as phonographs and radios. Latham chose to structure her project around the RCA theremin,1 the first electronic instrument to be commercially marketed in the U.S. For Latham, the theremin serves as a lens through which to examine both the paradox of musical labor and the broader societal implications of the commodification of music.

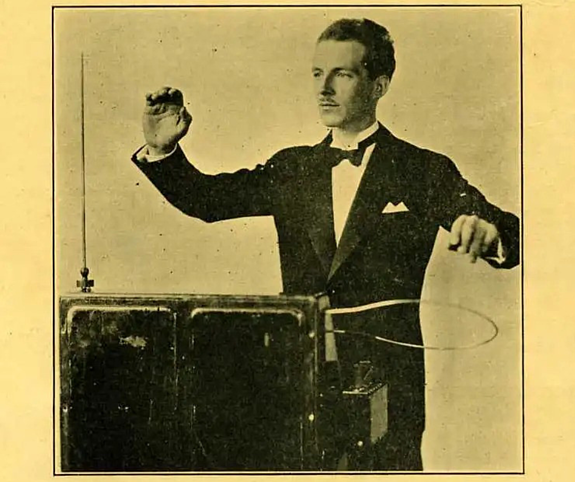

The RCA theremin is a highly unusual electronic instrument, notable on account of it being played without physical contact from the musician. The instrument consists of a box with two metal antennae that generate an electromagnetic field. The performer interacts with the theremin by moving their hands in the vicinity of these antennae, which disrupts the electromagnetic field. This action produces the theremin’s unique, almost squealing sound, which New York Times music critic Harold C. Schonberg once described as being like that of a cello “lost in a dense fog, crying because it does not know how to get home.” The instrument’s pitch is controlled by vertical hand movements and volume is adjusted by horizontal motion. The positioning of the hands and fingers is also consequential for the sound produced. Thus, although the musician does not actually touch the theremin, their body essentially becomes an extension of the instrument while playing. Although the theremin might seem unusual, its distinctive sound may be more familiar than you first think: the instrument was used in the 1950s film The Day the Earth Stood Still to create the ominous sound that signified the appearance of the evil alien.2

The theremin first arrived in the U.S. alongside its inventor, Leon Theremin, at the end of 1927. Theremin came to the U.S. from his native Leningrad, where he developed the instrument while working as a scientist. His entrance onto American soil was well-timed: prior to the Wall Street Crash, in the years 1928 and 1929, music technologies such as radios and phonographs were immensely popular.

Yet at the time, there was a backlash against so-called mechanical music. Latham explains that much of this stemmed from those who stood to lose money from the technology’s development, such as composers. Early copyright laws meant that a record company could buy one copy of sheet music, make a recording, and then replicate it ad infinitum, selling as many records as they pleased. It wasn’t until the Copyright Act of 1909 that they had to pay composers a flat rate for each mechanical reproduction.

Amidst the controversies surrounding copyright, mechanical music and so-called mechanical music-makers were imbued with the characteristic of soulless regurgitation, and were presented as being harmful to the tradition and practice of music. John Philip Sousa, in 1906, described such machines as a “… substitute for human skill, intelligence, and soul,” and in the melodramatic manner of the alarmist (a label to which he fully submits), likens them to the English sparrow:

“which, introduced and welcomed in all innocence, lost no time in multiplying itself to the dignity of a pest, to the destruction of numberless native songbirds, and the invariable regret of those who did not stop to think in time.”3

In an effort to combat the criticism leveled at mechanical music, much of the repertoire performed on the theremin consisted of popular classics, such as Schubert’s “Ave Maria” and “Air of Dalila” by Saint-Saens. “That couldn’t be further from so-called ’new’ music that you would expect from the likes of Stravinsky,” she tells us. The reason for this is to associate the theremin with so-called bonafide music. “They were trying to emphasize that this is music,” she continues. “This isn’t noise. They were trying to legitimize themselves by appealing to traditional tastes. But then the modernists did not like it for that very same reason. So really, the theremin could not win with either crowd!”

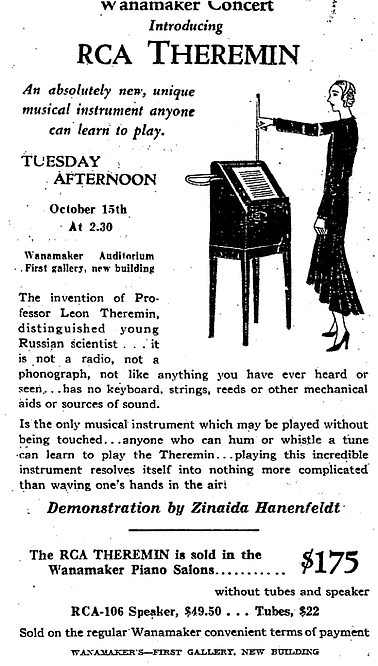

Despite the negative perception of the instrument with some audiences, by 1929, the theremin was being intensively marketed to consumers. This marketing is a key ingredient in Latham’s research, as it embodies the tension between labor and leisure. The marketing of the theremin suggested that it would offer the joy of music without the hard work needed to become proficient.4 For example, one advertisement reads:

“Without keys, or bow, or reed, or string, or wind, without material media of any kind—anyone can make exquisitely beautiful music with nothing but his own two hands!”5

In these advertisements, music is implied to be a labor-intensive endeavor from which the hard work can be removed, but other, contemporaneous marketing campaigns for household appliances present music in a very different light. These ads, for products such as vacuum cleaners and washing machines, name music and dancing as entirely pleasurable pursuits to which consumers can escape after automating their household labor. Again, the question remains of the precise position that music occupies within this society. Is it a leisure activity, or a chore?

While the theremin’s marketing blurs the lines between music-as-leisure and music-as-labor, Latham describes it as being inherently based on a lie: the theremin is, in fact, very difficult to play! In her discussion of this, Latham reflected on an interview that she conducted with Lydia Kavina, a prominent figure in the world of the theremin: she is famous as both an educator and performer of the instrument. Kavina, who is also the grand-niece of Leon Theremin himself, described to Latham the challenges associated with mastering this unique instrument. She emphasized that any tiny movement made by the player affects the sound of the theremin, stating that this leaves little room for performative gestures of any kind. “So no classic rock style poses!” adds Latham. Kavina had to dedicate significant skill and practice to excel at playing the theremin. Likely as a result of this, the instrument is not commonly used today. It still maintains a niche but dedicated fan base that appreciates its complexity: “they certainly do not perceive it as easy to play,” Latham tells us.

Latham’s research also touches upon a second lie inherent in the theremin’s marketing, which again surrounds hidden labor. Advertisements for the theremin were geared towards a very particular sector of society: white, middle class American women. But other women, often immigrants or those from less affluent socioeconomic backgrounds, were employed in the production of these technologies. This often-overlooked workforce of women labored in factories for very low wages, due to the fact that they could be paid less than their male counterparts. “Many of the workers manufacturing the components that went into radios and theremins were women,” says Latham. “People have cultural memory of women, especially immigrant women, working in factories for the textile industry, and this was happening in the realm of music technology too.” Yet the marketing brushes over this, presenting the technology as if it operates entirely independently of human labor. “When it seems like music technology, or a technology in general, is doing some kind of work for you, making you a better musician, I always aim to ask ‘what’s the other side of that? Where is the labor actually happening?’,” Latham says.

Using music in this way, as a lens through which broader questions about contemporary society can be interrogated, feels natural for Latham. This is due to the strong personal connections that individuals often form with the music that they make and the music that they love. “While people may also feel strongly about other forms of art like paintings or TV shows,” she tells us, “the unique intensity of the bond that they have with music creates a potent platform for exploring societal issues. It is this investment that makes music a powerful way to ask wider ethical or political questions.”

Moving back to Bach allows us to recognize the harmonies that exist between the ideas exemplified in his music and those that permeate Latham’s work. The German composer’s implied polyphony technique, which simulates an ensemble of musicians by means of a single instrument, might be considered an early form of music technology and a precursor to the theremin, capable of creating an effect similar to the modern-day mixing desk. For a listener enjoying Bach’s music, the technique might seem effortless, but there is, in fact, a great deal of skill involved in its successful execution. Again, juxtapositions between perception and reality proliferate, in the same way that Latham’s research reveals both the hidden truth of the complexity of the theremin and the often-overlooked nature of musical labor. A final comparison can be drawn with the help of an experimental research study conducted with real listeners to Bach’s music.6 The study highlighted that the German composer’s use of implied polyphony had a significant impact: it enhanced the aural appeal of his melodies even when they were played mechanically, without added expressiveness from a performer. In many cases, passages containing implied polyphony were considered to be more engaging by audiences, especially when the polyphony created simultaneous, linear streams of sound. Similarly, exploring the conflicting concepts entwined in Latham’s research, of music-as-labor and music-as-leisure, brings about a richer, and indeed more captivating, understanding of early twentieth century society.

Clara Latham is Assistant Professor of Music Technology at Eugene Lang College in New York City. She is currently the Martin L. and Sarah F. Leibowitz Member and Edward T. Cone Member in Music Studies in the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study. Her research focuses on the relationship between music, technology, and labor in the history of electronic music. Her articles have been published in The Journal of Musicology, Sound Studies, Women & Music, and The Opera Quarterly.

[1] The acronym RCA stands for the Radio Corporation of America, who manufactured the theremin.

[2] Unsurprisingly, given Latham’s research questions, the theremin can itself be considered something of a paradox. It does not straightforwardly fit into the classification of a musical media (like a tape and radio) or an instrument (such as a traditional violin or piano). Latham describes theremins as “objects in-between—an example of a media being used as an instrument.”

[3] Sousa, J. P. (1906) “The Menace of Mechanical Music” in Appleton’s Magazine Vol. 8, p. 278

[4] Other new electronic instruments, such as the autoharp, were marketed similarly. Latham describes the autoharp as the Guitar Hero of its day, since it automatically creates chords with the press of a button.

[5] RCA Theremin promotional brochure, Radiola Division, Radio-Victor Corporation of America, 1929.

[6] Davis, S. (2006) “Implied Polyphony in the Solo String Works of J. S. Bach: A Case for the Perceptual Relevance of Structural Expression,” in Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 23.5, pp. 423–446.