The History and Future of the Historical Studies - Social Science Library

Last year, as yet another attempt at repairing the leaking roof of the Historical Studies - Social Science Library loomed, the Institute reached out to me to study the problem. I researched the facts of the design, current problems, and possible solutions. Here is what I learned:

Design Process

In the late 1950s, the idea for a new library arose. A committee was formed in 1957 and architects were contacted, including Richard Neutra, Louis Kahn, Edward Barnes, and Robert Venturi. Marcel Breuer, who had just completed the Institute’s Member housing, made a proposal but it was rejected. Princeton architect Kenneth Stone Kassler proposed an underground building, which was also rejected.

Ultimately, Wallace Harrison of Harrison & Abramovitz, who had recently completed Robert Oppenheimer’s beach house on St. John, Virgin Islands, was approached. He accepted the commission in April 1960. At the same time, Harrison’s lifelong dream of designing a new Metropolitan Opera House was about to be realized. Meanwhile, Nelson Rockefeller had just asked Harrison to start work on design of the Albany Mall. Harrison had big projects to attend to.

Harrison’s effort was plagued from the beginning. In March 1961, the Committee "was unanimous in finding that the architects have so far failed to come to grips with the specific problem of [the] library, and even with the general problems of a library."1 Subsequently, the "question was raised whether the prudent course...might not be to cut [their] losses and look for another architect, one who could find the time and would be willing to give closer attention to [their] problems.”2

By April of that year, an excerpt from the Trustees' minutes notes that “Mr. Harrison runs a very big office, which prevented him from spending much time on the Institute problem. He assigned a younger man, Mr. Dudley, to the job.”3 In December, a "Mr. Wiseman" had replaced Dudley. By March 1962, a “Mr. Harris” arrived, and the Library Committee noted, "New plans...showed little regard for the work previously done by the committee, and offered, as Mr. Harrison’s current solution, the idea of a glass pavilion which the Committee unanimously rejected."4

Finally, in October 1962, a design that adhered to the desired program and interior organization was approved. Oppenheimer proposed a second floor as a means to provide future flexibility but there were no funds for it at the time. Drawings were hurriedly completed and construction began in June 1963. The building was completed in 1965.

Roof Failure

The design of the roof was innovative, first of its kind––and never to be repeated. By 1967, the roof had begun to leak.

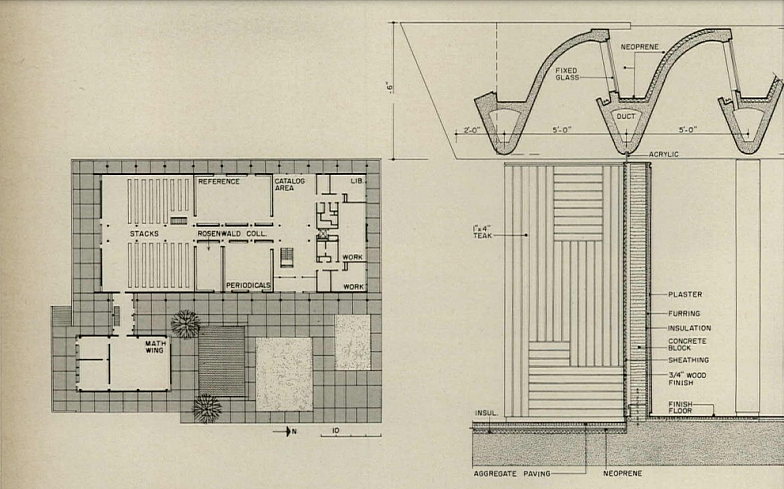

Some background on the building provides some context for its issues. The roof was designed as a set of concrete beams providing structural support and incorporating air conditioning ducts, glass skylights, electric light, and weather protection in one architectural element. There are eighty concrete beams5 and more than a thousand north facing skylight windows. Cove fluorescent tube lights cast into the beams provide light at night: on dark days, the beams themselves are hollow, designed as ducts to bring tempered air into the space through slots under the skylight windows.

However, this ambitious integrated system would prove to be unsuccessful.

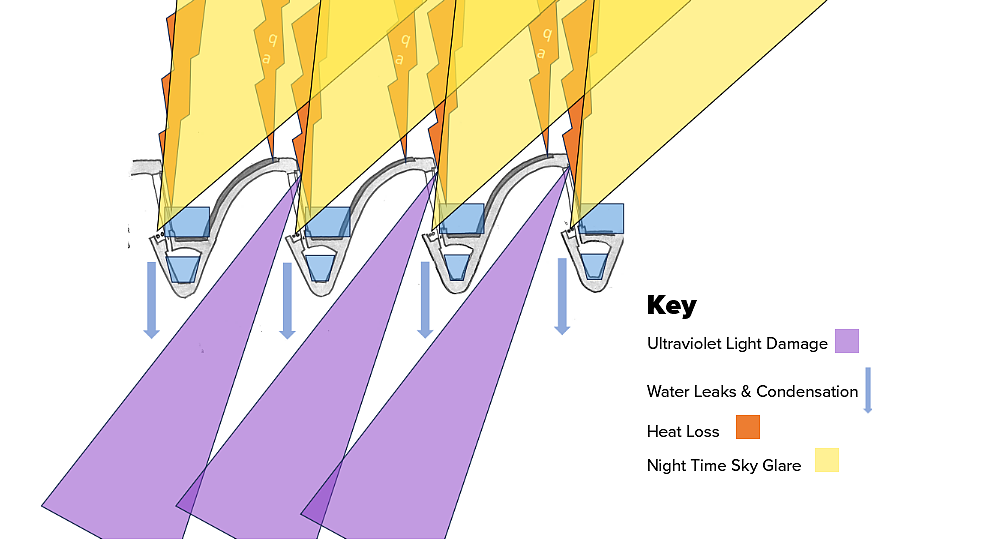

One of the most concerning failures is its susceptibility to the elements. The glass skylights are set deep into the valleys formed by the curved beams. The glass is set directly into the concrete. During rainstorms, the valleys fill up; rising water infiltrates under the glass, through cracks into the concrete beams, into the ducts, and down to the library below. On other days, condensation forms on the single pane glass, dripping into the ductwork and through concrete. There is not enough depth in the beam design to accommodate window frames or double glazing. Repeated replacement of the waterproof roofing in past years was not able to prevent leaks because it could not solve the fundamental geometric design problem of the placement of the glass at the bottom of the valleys.

Additionally, the roof is not insulated. There is no way to add insulation without blocking or reconstructing the openings for the glass. The combination of single pane glass and an uninsulated roof means that energy use dramatically exceeds the norm. The library, therefore, is an expensive building to operate: It uses 43% more energy than a comparable building of the same size.

Moreover, due to this design, the library books have faded and show signs of UV damage. Ultraviolet protective film has been applied to the glass in some areas, but it is peeling off. The original fluorescent lighting has been largely replaced with various LED bulbs. Uneven light color variation is apparent even on the brightest days.

But these are not the only problems: the skylights illuminate the night sky, to the dismay of IAS neighbors, visitors to the Princeton Battlefield Park, migrating birds, and local fireflies. On this topic, here is a quote from Oppenheimer himself, from Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman’s biography American Prometheus:

“…the library had an innovative roof that used glass louvers set at an angle. In daytime, this provided ample sunlight. But at night, the library’s electric lighting shone upward. From a distance the whole sky seemed to be lit up by a great fire. When David Lilienthal praised the beauty of the new library’s setting and the spectacle it created at night, Robert gave him a 'little-boy grin' and said, ‘The library is beautiful, and the setting. It is also an illustration of how we don’t anticipate the most obvious consequences. This happened to us in a major way with the bomb in Los Alamos. As for the ceiling for the library, we wanted the best light, the light in just the right way….In the daylight it turned out to be wonderful. But no one, not one of us, foresaw that not only would light come in, but it would go out—into the sky.’”6

Why can’t the roof be fixed?

The tragic mistake in the design of the original building was the attempt to combine structure, weatherproofing, sky lighting, ductwork, and electric lighting in a single solid concrete element. Today, to imagine replacing the roof or fixing the roof is to imagine removing the concrete structure, decapitating the building in order to start over again. The geometry, shape, and dimensions of the structure cannot be modified to raise the glass out of the valley, cannot be thickened to receive an adequate glass frame, cannot be insulated to meet goals for energy use, and cannot be angled to improve roof drainage. Even then, it would still not solve the “sky on fire” problem that Oppenheimer identified.

Put simply, it cannot be done. Covering the roof is the only viable way to proceed to save the building.

What can be done to preserve the building?

Here are some suggestions. The building can be sealed to protect it from weather. The teak facades can be restored, and large panes of glass along the exterior walls can be replaced with double glazing in frames that match the original dimensions and finishes. The open plan and flexible spaces of the interior will remain. Finishes and furnishings, terrazzo floors, wool carpets can be restored. At the same time minimal interventions to the mechanical systems, plumbing, drainage, and surrounding terraces can improve overall accommodation and enhance resilience.

What about the light? The good news is that LED lighting now available can perfectly simulate changing aspects of daylight with minimal energy use. My recent work with James Turrell on a Skyspace in New York revealed a world of lighting technology that did not exist sixty years ago. New lighting can precisely replicate the original, and can also explore and create new perceptual experiences.

In sum, the building can be saved and restored to its original elegance and serenity. The best way to do this would be to cover the roof.

By covering the roof and introducing modern lighting systems, the Library’s continued use and presence is ensured. A new structure over the roof can act as a base for the much-needed additional space above and can be done in a timely and economical way. After all, a second floor was contemplated in the original project. The annex was reconfigured in 2009, and a compatible addition to the archive was completed in 2014. Adding volume without using open land is also a net gain in environmental terms. With the right design guidelines, the addition can be successful.

My proposed guidelines for the addition, in order to maintain the spirit and look of the original, are as follows:

- Maintain a respectful and compatible relationship to the existing library

- Maintain the strong horizontal lines of the original building

- Use teak wood exterior paneling where appropriate and continue use of white banding

- Limit the amount of glass, especially on west and south facades

- Minimize the height of the addition

Conclusion

Fixing the roof is now a race against time. Climate change is bringing sudden disastrous rain and snow events. A single intense rainstorm could destroy the collections and much of the building. In the sixty years since the completion of the Library, the importance of sustainability, energy conservation, and respect for the natural environment has grown. Going back to an unsound concept is not the way to go forward.

Architecture is an art that accommodates change over time. It must be usable and useful to survive. Keeping up with the times may require complete renovation, adaptive reuse, new systems, or new additions. The best buildings are not static. They reveal their history as they change over decades, or millennia. A structure that cannot accommodate change is destined to perish.

Architectural design is a collaborative process. Buildings are created for human use. We are now engaged in that process of collaboration to achieve the best result: preserving the vision of the building, its use and its collections, its spirit and atmosphere—respecting the past and opening a path to the future for the Institute.

- "Report of the Library Committee, 1961" in "Library -- Harrison and Abramovitz, 1960-1965," Box: 40, Folder: 13. Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, N.J.). Director's Office. General records, 00022. Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center."

- Ibid.

- "Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Board of Trustees, April 21, 1961," Box: 10. Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, N.J.). Board of Trustees records, 00118. Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center.

- "Summary of relations between the Institute and the firm of Harrison and Abramovitz, April 1960- March 1962 by H. Cherniss, M. Meiss, and A. Weil" in "Library -- Harrison and Abramovitz, 1960-1965," Box: 40, Folder: 13. Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, N.J.). Director's Office. General records, 00022. Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center.

- The concrete beams were to be precast and brought to the site. The contractor could not find a precasting firm and had to devise a method to form the beams on site. The first few dozen were found to have defects which were repaired, but the consequence was that the natural concrete surface, designed to be exposed, was painted white.

- Bird, Kai and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. (New York, A.A. Knopf, 2005), 580.

Frances Halsband is a founding partner of Kliment Halsband Architects. She has served as Architect Advisor to the Brown University Corporation, architectural review panel member for Harvard University, and architect advisor to Smith College. In those roles, she assisted in the selection of architects and was a peer reviewer for continuing design work. She is a former Commissioner of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. She was dean of the School of Architecture at Pratt Institute, and Visiting Professor of Design at Columbia, Harvard, Penn, and UC Berkeley. Frances received a Bachelor of Arts from Swarthmore College, a Master of Architecture from Columbia University, and an Honorary Doctorate of Design from the New School of Architecture and Design in 2019. In 2023 she was inaugurated as the 61stChancellor of the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).