"Life is a term, none more familiar. And one almost would take it for an affront, to be asked what he meant by it," writes John Locke. But he immediately adds: "And yet, if it comes in question, whether a plant, that lies ready formed in the seed, have life; whether the embryo of an egg before incubation, or a man in a swoon without sense or motion, be alive, or no? It is easy to perceive, that a clear distinct settled idea does not always accompany the use of so known a word, as that of life is."

For Locke, then, the problem is above all that of determining the limits of life: its indistinct beginning in the seed or the egg (around which arguments continue today, in debates about voluntary termination of pregnancy), and its uncertain end in unconsciousness without feeling or movement (questions that would be subsequently raised around the recognition of brain death).

But the attempt to define "life" also raises concerns of a different order, bound up with the multitude of meanings encompassed by the word itself. It denotes at once a property of organized beings, a set of biological phenomena, a time that elapses between birth and death, and a range of events that fill this temporal space, to say nothing of metonymic or metaphorical uses when we refer to the lives of great men, or the life of objects. Are we talking about the same thing in each case? Is the life of a human being a fact of the same order as the life of the cells that constitute it? To be sure, the commonsense understanding does not tangle itself up in complications, and everyone understands more or less what is meant, amid the multifarious senses of the term, by expressions such as life sciences, life expectancy, life in the country, or the life of ideas, in each of which the word has a different meaning. The same cannot be said, however, of philosophers, who appear at an impasse when attempting to consider life as conceived, for example, by a biologist together with life as interpreted by a novelist.

The problem is articulated with clarity by Georges Canguilhem: "Perhaps it is not possible, even today, to go beyond this first notion: any experiential datum that can be described in terms of a history contained between its birth and its death is alive, and is the object of biological knowledge." This seems a simple definition. Yet it brings together quite heterogeneous elements, which highlight a semantic tension. Knowledge and experience, biology and history: this is the great dualism inherent in life. And Hannah Arendt pointed to a similar duality: "Limited by a beginning and an end, that is, by the two supreme events of appearance and disappearance within the world, it follows a strictly linear movement whose very motion nevertheless is driven by the motor of biological life which man shares with other living things and which forever retains the cyclical movement of nature. The chief characteristic of this specifically human life, whose appearance and disappearance constitute worldly events, is that it is itself always full of events which ultimately can be told as a story, establish a biography." Cyclical movement of nature and worldly events, biology and biography: these are the two series that make life an entity at once overdetermined in its material dimension and indeterminate in its course. In effect, one incorporates humans into a vast community of living beings, on the same level as animals and plants, while the other makes them exceptional living beings by virtue of their capacity for consciousness and language.

Can this binarism be resolved? Is it possible to think of life as biology and life as biography together? For two thousand years, philosophers have applied themselves to this question. They have successively considered life as animation of matter, following Aristotle, as a mechanism generating movement, with Descartes, and as a self-maintaining organism, as did Kant. They thus moved from a vitalist representation to a mechanistic interpretation, and finally to an organicist approach, each with a different medium: the soul or breath, then the body and fluids, and finally the organs and the internal milieu. However, the point in each of these various interpretations was to pursue an interrogation of the relationship between the living and the human, between the infrastructure of the former and the superstructure of the latter, as it were. For Hegel in particular, "'life' is a transitional concept that relates the realm of nature to the realm of freedom," as Thomas Khurana puts it, since while it is constrained by biological elements it can, through a process of self-organization, produce the autonomy required for the realization of a biographical journey.

In contrast to these earlier attempts to articulate the two dimensions of life, over the last century, the opposition between the two trends has hardened, leading to an apparently irremediable division between the two.

As regards life in the biological sense, it was in the mid-twentieth century that, through the unlikely intervention of quantum mechanics theorist Erwin Schrödinger, the study of living beings shifted in scale, and hence also in perspective. Henceforth, the physicist turns biologist, his analysis descending to the molecular level, his method borrowing from thermodynamics, and atomic structure becoming a code whose innumerable permutations make possible the diversity of living beings and the creation of order out of entropic chaos.

On the Inequality of Lives

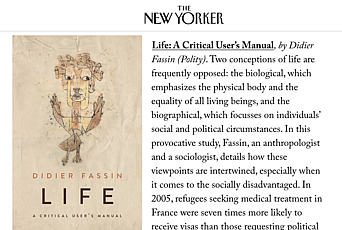

"The subject of this text is indeed as the title states: it deals with life–and with lives. It would be easy, and certainly on one level true, to state that this is the guiding principle of a career that began in medicine and then diverted to anthropology: in turning from the teachings of biology to the gathering of biographies, I have moved from the life of organs to the life of human beings. But there is more to it than the fortunes of a professional trajectory. For my way of scrutinizing life through forms of life, ethics of life, and the politics of life is not neutral. It is marked by the theme of inequality–the inequality of lives which, from my childhood in a public housing project to my discovery of non-Western societies through the extreme poverty I encountered in Indian cities, has formed my worldview. In fact this book could, perhaps more explicitly, have been titled 'On the inequality of lives.'"–DF, Life: A Critical User’s Manual, “Acknowledgments”

While validating this theory, the discovery of the DNA double helix a few years later constituted the foundation for a new conception of life, now based on information and its replication. Fifty years later, the recent decoding of the human genome has further refined this concept. Even contemporary epigenetics does not fundamentally challenge this paradigm, since the influence of context on genetic inheritance, which it seeks to account for, operates through molecular mechanisms that modify the expression of genes. In other words, biochemistry and biophysics, which are now integral strands of biology, produce theories based on an increasingly intensive molecularization of the living matter, albeit not excluding systemic approaches at a higher level of complexity in microbial populations. At the same time, research into the origins of life focuses both on the emergence of living beings on Earth during the Precambrian period and on the possibility of finding signs of life elsewhere in the universe. This research strives to understand how inert molecules were able to transform into organic molecules with the capacity to replicate themselves so as to generate nucleic acids, and seeks to assemble spectral libraries drawn from living terrestrial organisms. On the one hand, microbiologists are searching for the "last universal common ancestor" of all cells, and the environment conducive to its transformation. On the other, astrobiologists seek "potential biosignature gases" that would point to the presence of life on the exoplanets of other solar systems. In both cases, science comes to meet the imagination of men and women, and the prospect of discovering the ultimate origin of life, or signs of extraterrestrial life, even in the form of molecules rather than identifiable beings, inspires dreams and drives requests for funding. In short, in the exploration of life as biological phenomenon, the shift from conjecture to experiment, from the macroscopic to the microscopic, and from bodies to molecules, has progressively reduced the understanding of life to its most basic material unit—an assemblage of atoms—while at the same time expanding it massively in time and space: human beings are, indeed, dissolved in a temporo-spatial network of molecular components of life which appeared several billion years ago and may be present in other parts of the universe.

With life as biography, we find a quite different story—more fragmentary, less cumulative. We can, however, identify certain moments, such as the arrival of the novel in literature, and some features, including an increasingly anxious questioning as to how one should write about life and lives. On the one hand, the novel, as it developed from the eighteenth century onward, constituted life for the first time not only as an interesting subject but also as a "detachable thing," as Heather Keenleyside puts it in her discussion of Tristram Shandy. It frames life as a more or less linear unfolding of events, through which the subjectivities of the characters are formed, whether in Jane Austen's novels of manners, Goethe's bildungsroman, or a little later, the great literary projects of Balzac and Zola, who reconstitute a society at a particular time through the life stories of individual characters more or less connected to each other. In its most complete as well as most radical expression, with Proust, the autobiographical account becomes life itself, a life magnified by the creative labor of writing: this is what he calls the true life, the life that, by virtue of convention and habit, we risk passing over, to the extent that one might die without ever having recognized it. On the other hand, in the social sciences, from the very beginning, alongside the important developments in theory and methodology by the founders of the discipline, the life story has played a central part, whether it be reconstituting the trajectory of a Polish peasant, in the case of William Thomas and Florian Znaniecki, or recounting the history of a Mexican family, as does Oscar Lewis. But it was particularly from the 1980s onwards that, as the reaction against structuralism came together with feminist critique and postcolonial studies, the demand arose, in anthropology as elsewhere, for recognition of individuals, their history, their truth and their words. The narrative turn was also a subjectivist turn. One should no longer speak in the name of subalterns, but rather make their voice heard - with the singular difficulty, particularly for historians, that their lives have often disappeared without leaving a trace in the archives. But a few decades later, a contestation of the life story and its identification with life began to emerge, both in literature, through a deconstruction of the narrative form in Samuel Beckett's work, and in the social sciences, in the form of Pierre Bourdieu's challenge to the biographical illusion. Life as a coherent form became an object of suspicion.

Two life lines, then. For the purposes of clarity rather than classification, let us call the first one naturalist, the second humanist. My aim, in attempting this brief description of how they developed, is to point out the existence of two approaches that appear, at least in the first analysis, increasingly irreconcilable. The life studied by the biophysicist no longer bears any relation to that imagined by the novelist, even if some novelists incorporate biological elements into the fabric of their narratives, and some biologists venture, with varying success, into literature. The objects astrobiologists deal with, namely the molecules that indicate a presence of life, bear little relation to the subjects encountered by sociologists, namely individuals who recount the facts of their lives, even if, in the first case, the search for some presence of life is not unconcerned with the search for non-human intelligence, and in the second, sociologists can make the life sciences laboratory the focus of their research. We are far from the Aristotelian, Cartesian, Kantian, and Hegelian projects.

Considering these vicissitudes of the concept, is an anthropology of life imaginable, or even desirable? Here we have to start from a paradox. Although anthropologists have always been interested in the lives of their interlocutors, in terms of both way of life and life stories, they have rarely made those lives a specific and legitimate object of their research. The lives that they studied synchronously, through the culture within which they unfolded, or diachronically, through the stories that reconstructed them, served as empirical material for their analysis of kinship, myths, social structures, religious practices, or political institutions. Even in its most embodied manifestations, such as biographies, the aim was principally to understand trajectories, situations, emotions. Life itself was rarely seen as an object of knowledge on the same level as the other categories constituting their discipline. It was a sort of vehicle or medium that allowed them access to concepts and realities deemed more significant or more relevant for the description and interpretation of societies.

In recent decades, however, anthropologists have started to construe life as object, principally considered in either the naturalist or the humanist form described above. On the one hand, within the context of the great body of research emerging from the social studies of science, life has been approached in the same way as by researchers in the biological, physical and even information sciences—in other words, as living matter. Anthropologists have analyzed the knowledge, practices and objects of life sciences, focusing among other things on genomics and epigenetics, stem cells and cell death, hereditary conditions and regenerative medicine, the development of artificial intelligence, and the use of neuroscience in criminology. In other words, they have been endeavoring to understand and interpret the leading-edge research into the various manifestations of life. On the other hand, in the more traditional domain of social or cultural anthropology, there has been a proliferation of monographs on the life of individuals based on the everyday detail of their existence, in geographical contexts that vary widely but are often marked by the ordeals of poverty, sickness, and misfortune. There have been studies focused on the death of children in Brazilian favelas and the affliction of extreme poverty in rural India, on the destitution of the Ayoreo Indians of Paraguay and suicide among the Inuit of northern Canada, on the feeling of loss in the aftermath of the civil war in Sierra Leone and the tribulations of wounded veterans returning from war in the United States. In these studies, life is generally presented not only in its subjective dimension, as experienced by these men and women, but also in terms of the objective conditions through which society contributes to shaping and treating it. In other words, apart from a few attempts to combine the naturalist and humanist approaches, for example in medical anthropology, where sickness sits at the meeting point of biology and biography, the two life lines have largely been deployed as parallel avenues of anthropological research. Yet these approaches are not conceived as anthropologies of life as such, but rather as anthropologies of life sciences and of life experiences respectively.

In order to render an account of life that does justice to the complexity of its multiple dimensions while at the same time representing it with a degree of unity, I therefore propose to analyze and relate three conceptual elements of those dimensions: forms of life, ethics of life, and politics of life. Each of these opens up an anthropological fact of life. Beyond the contradictory interpretations proposed by exegetes, forms of life, as outlined by Wittgenstein, reveal the tension between the specific modes of existence and a common condition of humanity: the experience of refugees and migrants offers one tragic illustration. Unlike the concept of the ethical life inherited from Greek philosophy, ethics of life extend Walter Benjamin's reflection on the sacralization of life as supreme good: the higher principle of humanitarian morality that consists in saving people threatened by disaster, epidemic, famine or war here collides with the opposite rationale based on the honor of sacrificing oneself for a cause on the battlefield, in a suicide attack, or by hunger strike. Finally, taking up an illuminating idea that was never fully followed through, politics of life reformulates Foucault's notion of biopolitics: contrary to the dogma of sacred life which should render it beyond price, it is possible to put a monetary value on human existence, and this varies according to the gender, social class, ethnic background, and geographical origin of the individual.

So, if it is true, as Perec suggests in Life: A User's Manual, that it is the pattern that determines the parts rather than the opposite, the theoretical framework behind each of these three concepts derives from a reflection on the treatment of human lives in contemporary societies. One theme underlies this reflection: inequality. As I hope to show, this theme binds together the biological and the biographical, the material and social dimensions of life—in other words, the naturalist and the humanist approaches. What I propose, then, is not an anthropology of life, which I deem an impossible project, but rather an anthropological composition formed of three elements which when assembled, like a jigsaw puzzle, reveal an image: the inequality of human lives.