Robbert Dijkgraaf on Covid-19, Science and Society

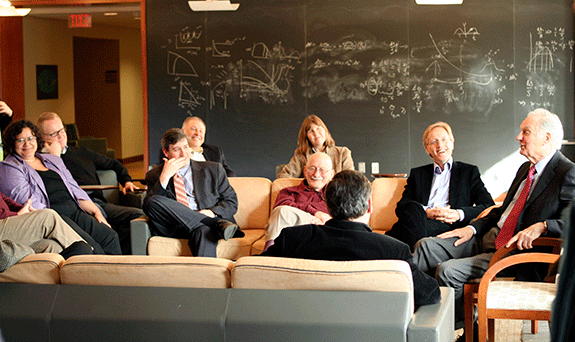

Robbert Dijkgraaf, Director and Leon Levy Professor of the Institute for Advanced Study, sat down virtually with Joanne Lipman, IAS’s Peretsman Scully Distinguished Journalism Fellow, to discuss the coronavirus epidemic, its impact on IAS, and the elevated role of science in society. This interview was conducted on March 25, 2020. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Joanne Lipman: What are your priorities for the Institute right now?

Robbert Dijkgraaf: The most important priority from the very beginning has been to keep the Institute community safe and well. And, very explicitly, not only our scholars, but also our staff and the extended Institute family.

JL: At a time like this, what role does the Institute play?

RD: We often talk about being a community of scholars in an abstract sense… but this time it has become much more concrete, taking care of each other. We’re trying to react as best as we can on the individual needs, which are quite diverse.

At the same time, we’re also supporting people who are able to keep their scholarship going. That’s our mission too. It’s also important for many people to keep on working. Although these are difficult times, there are virtual seminars, virtual working groups, even virtual tea times. In fact, in the physics seminars I saw some of my friends and colleagues from distant universities. So, we are able to connect to a wider audience.

I’ve also noticed a wonderful initiative that Alondra Nelson, Harold F. Linder Professor in the School of Social Science, took called the “Coronavirus Syllabus” to provide background literature for scholars studying the current crisis. It is great to see the academic world coming together.

JL: You hear about scientists who have done remarkable work at a time when they are isolated or at a time of great stress. Shakespeare, for example, lived during the Black Plague, and it was a fruitful and productive time, because everyone was isolated.

RD: Again, this is hardly an ideal circumstance but there is the famous story that physicists have always been told about Newton basically inventing modern science when he was sitting under the apple tree at his home, having had to leave Cambridge following an outbreak of the bubonic plague. I think this is setting the bar rather high.

The big difference is, when Shakespeare or Newton had to be in self-isolation, they weren’t checking their phones every minute.

JL: Ah, yes.

RD: Because we are still in constant communication, I would be surprised if we got kind of a creativity bump out of this. I think that would be probably a bit too much of a glass-half-full view. Personally, I certainly feel quite overwhelmed by it all.

But I am heartened by the past. As an institution, we went through grave crises before. Think about the very first scholars who came here, right in the Depression, with all the political turmoil in Europe, and yet at that time believing that the most important contribution they could make is to long-term thinking about the world and the universe.

When we look back at these many troubled periods, we can conclude with confidence that the mission that we are involved in has stood the test of time. There is a need for looking through this mist, this thick fog that now surrounds us.

The History Working Group is a Member-led initiative that mobilized in early 2017 in response to President Trump’s executive orders banning travel and immigration from seven predominantly Muslim countries. The group has documented how IAS responded to similar challenges in the past, finding its ethos as a place of refuge and active engagement with the world.

Watch "A Refuge for Scholars: Contemporary Challenges in Historical Perspective" now.

JL: How does the basic research at IAS impact public health?

RD: There are definitely relevant areas of research. Biologists study the mathematical modeling of the genetic diversity and spread of viruses. Social scientists study science policy, to which extent the voice of science is heard within policy, public health, and the most fragile segments of society. Historians and scientists shed a light learning from previous pandemics.

On the other hand, I think this crisis makes clear that you can’t improvise research. The only way to address current issues from a scientific point of view is to have done the research many years ago when it might have looked less relevant.

JL: You’ve been a proponent of open access to scientific discoveries. What role does that play in the current crisis?

RD: I find it encouraging that the scientific community has come fast together. There is a rapid exchange of information. It’s remarkable to see that in the biomedical field researchers are now using open access. They’re sharing information that’s not behind pay walls.

Again, a crisis clears the mind. It’s totally obvious now that if somebody finds a certain piece of data or insight it should be accessible immediately. Some fields have been more open to sharing this information than others. I hope at least that this makes it crystal clear that there is no particular advantage of locking up scientific information. It should be accessible to everyone.

JL: You wrote recently, “It is reassuring to see how quickly the world of science has united …. Experts speaks largely with one voice. But the differences in how this voice resonates in policy are immense… Where science is a continent, government is an archipelago.”

RD: It is. There’s a unified voice of science. There’s less of a unified voice of policy.

JL: Should there be a more uniform policy for the United States? It is scattershot here.

RD: It’s totally scattershot, with even large divisions among states and cities. There’s a natural authority that comes from the voice of science, but it has to be amplified. The people in the front line are trying this, they’re doing their very best in very difficult circumstances. If one thing has become clear, that is the public at large really is desperate to hear these scientists speak out. The trust in science is strong.

JL: What are the long-term implications of COVID-19 for the Institute, and for attitudes towards science?

RD: First of all, the Institute and the research community, as all others segments of society, will be impacted by the unavoidable economic downturn. But, if anything positive can come out of this, I hope this crisis will reinforce the importance, the reliance of society on science and scholarship. That it will clarify the minds of those in government that they need evidence-based advice. There is a whole catalogue full of other terrible things that can happen to the world that scientists and scholars think about... whether it’s an economic, environmental, or nuclear crisis. So, this can also be a valuable peek into the future, showing the interconnectedness of the world and the fragility of societies. And the need of the thoughtful voice of science.

We are in this paradoxical situation where you want to jump into the here and now with so many tragedies happening. But the one thing that we can do at a place like the Institute is to be a point of reflection. We have to try to achieve the bird’s-eye perspective, and that’s very difficult to impossible to do in a moment of despair. But that’s the role of scholarship, to have this kind of social distancing to the world, to the present, in order to see the bigger picture.

JL: On a practical note, what do you see for the campus in terms of opening up again? What’s your expectation at this point?

RD: We’re driving very fast through a thick fog. It’s very difficult to predict the future. I think, we’ll just be practicing watchful waiting. We take it week by week.

JL: Is there any message that you would like to share with the Institute community and friends?

RD: Well, the one thing I find most impressive and uplifting these days is the resilience of our community, how people have been taking care of each other. Part of the spirit of the Institute is that we count on the self-organizing skills of our scholars and our staff, and that spirit shines through splendidly.

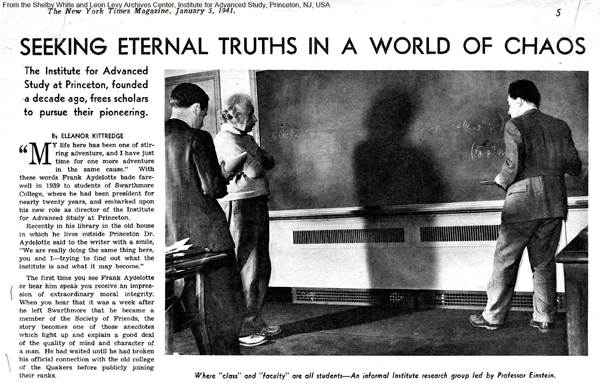

The Institute has been pretty resilient through the many decades. We survived some very intense storms. I just shared an image of the New York Times Magazine from 1941, a beautiful picture of Einstein in front of the blackboard. And the title was “Seeking Eternal Truth in a World in Chaos.” And I realize, wow, 1941 and Einstein was thinking about space and time.

Courtesy of the Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives at the Institute for Advanced Study

It’s a terrible storm, but, again, my most important message to members of the community is: take care of yourselves and your families and let us know what IAS, if anything, can do to help. There are many factors at play right now and the biggest one is to make sure we all remain as physically and mentally healthy as possible.