To “Write as I Paint My Pictures”: Paul Gauguin as Artist-Writer

“When Paul Cézanne wants to speak ... he says with his picture what words could only falsify.” In The Voices of Silence (1951), French author and statesman André Malraux expressed his view that the Post-Impressionist painter could only “speak” with paint, not with words (his letters, according to Malraux, amounted to no more than a catalogue of petty-bourgeois concerns). This gives a fair idea of the reaction that a painter who tried their hand at writing could expect in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But what did this mean for artists who wished to respond, verbally, to their critics, or for whom writing and painting were equal components of an interdisciplinary practice?

My research at IAS investigated Paul Gauguin’s (1848–1903) solution to this problem. Although skeptical of critics (he claimed that art needed no verbal commentary), the French Symbolist painter, best known for his vibrant paintings of Tahiti, nonetheless wrote a good deal. His literary output included art criticism, satirical journalism, travel writing, and theoretical treatises, most of it unpublished in his own lifetime. He was adamant, however, that none of this writing amounted to “art theory” as practiced by literary critics. Instead, his aim was to “write as I paint my pictures”—that is (he would have us believe) spontaneously, without regard to academic convention, and in a manner suited to the “savage” he hoped to become as a result of his relocation to French Polynesia in the 1890s. Conscious of the contradiction inherent in using words to defend the visual, he insisted: “I am going to try to talk about painting, not as a man of letters, but as a painter.”

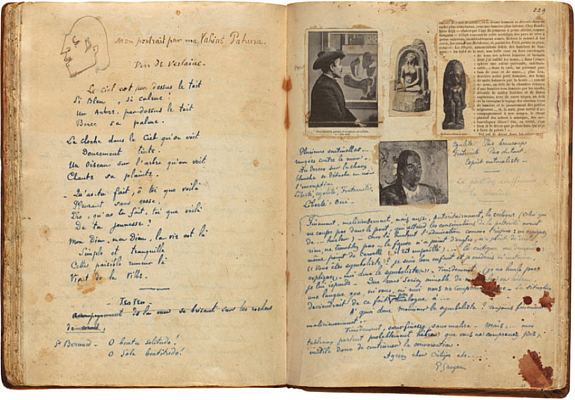

A hybrid figure, at odds with the colonial government yet necessarily an outsider to the indigenous community in Tahiti, Gauguin used his status as an artist (that is, as we have seen, one who is typically denied access to linguistic expression) to enhance his “primitive” credentials. For instance, he described his manuscript Diverses choses (Various Things, 1896–98) as consisting of “childish things”: “Scattered notes, without sequence like dreams, like life made up of fragments: and because others collaborate in it”. These qualities of fragmentation, collaboration, and childlike spontaneity can be seen in one of several double-page spreads of collaged images and text, which appear artless (like a scrapbook) but are in fact very carefully put together to project a particular self-image.

In an imaginary “letter to the editor” (signed Paul Gauguin, at bottom right), he attacked art critics who seek to categorize and label artistic styles and movements. Yet on the same page, he pasted several newspaper cuttings (which include a review of his work, and photographs of himself and his artistic creations)—undercutting his claim that artists have no need for the support of critics.

He minimized this contradiction, though, by using a careful arrangement of text and image to shift the focus away from European art criticism, and towards his affiliations with poetry and the “primitive.” At the top of the left-hand page, he has drawn a simplified, stylized self-portrait, which he falsely attributed to “my vahine [mistress] Pahura,” as if to confirm his savage credentials. He placed it above a transcription of the Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine’s confessional poem (“The sky is, above the roof, so blue, so calm”)—a poem celebrating freedom and the beauty of nature, written while Verlaine was in prison for shooting his lover and fellow poet Arthur Rimbaud. The poem is followed by a reference to the twelfth-century Cistercian monk Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, quoting his praise of solitude (“blessed solitude, only blessing”). By placing his self-portrait at the head of the page, above these borrowed texts, Gauguin links his own exile from “civilization” to the virtuous isolation of the pious monk or the incarcerated poet.

On the right-hand page, the newspaper article at top right juxtaposes one of Gauguin’s sculptures, intended to evoke Tahitian idols, with a passage from Baudelaire’s prose poem Plans, evoking a tropical landscape, and directly compares painter and poet in terms of their rejection of materialism and experience of exotic travel. In the cluster of photographs, Gauguin placed, at left, a studio portrait of himself in profile—which closely mirrors the profile of his “savage” likeness on the opposite page—alongside his representations of Tahitian women. In this photograph, he stands in front of the seated figure from his painting Te Faaturuma (The Brooding Woman), whose pose reflects that of the female Buddha in the reproduction of his Idol with a Pearl carving immediately to the right; directly below, a cropped photograph of Vahine no te tiare (Woman with a Flower) focuses attention on the androgynous face of the woman, whose contemplative demeanor echoes Gauguin’s own static pose.

Again, this visually cements his identification with the Tahitian figures. Avoiding the dull linearity of the critic, who relies on logical explanations, Gauguin’s various textual and visual allusions build up a multifaceted portrait of himself as both poet and savage—using a variety of media, authorial voices, and literary registers (aphorism, criticism, poetry, polemic). This is what he meant by writing “as a painter.”

As in his self-portraiture, in his writing, too, Gauguin experimented with adopting different identities, sometimes writing under the guise of a fictional “ancient barbarian painter,” whom he named Mani Vehbi Zunbul Zadi. In Le Sourire, the newspaper that he wrote, printed, and distributed in Tahiti, he assumed, in the opening issue, the identity of a female theatre critic (just as he drew, in Pahura’s self-portrait sketch from Diverses choses, as if through the eyes of a young girl). In a review of a one-act play by a Tahitian woman, he wrote: “I must confess that I am a woman, and that I am always prepared to applaud one who is more daring than I in fighting for equivalent moral freedoms to men.” In the voice of the female reviewer, he goes on to describe how Anna, the play’s protagonist, believes in friendship and sexual freedom, but mocks romantic love and marriage.

In a contradictory blend of sexism and feminism, combined with self-interest, that is typical of Gauguin, the review ends with a call to arms, entreating men to help liberate women, body and soul, from the enslavement and prostitution of marriage, since “we women don’t have the strength to free ourselves.” It is signed Paretenia—Tahitian for “virgin.” At the base of the page, next to the byline Paretenia, is a sketch of a puppet theater, and, alongside, one of customers rushing to buy Gauguin’s newspaper, with the caption “Hurry, hurry, let’s go and find Le Sourire.” Via the guignol, an emblem for his own satirical broadsheet, Gauguin affiliates his publication with the subversive morality of the (probably fictional) Polynesian theater.

Gauguin aligned the visual artist with the “primitive” and the writer with the “civilized” but was ambivalently suspended between the two. He lamented the impact of European civilization on Polynesian society, yet remained implicated in the imperialist culture that he denounced. What I am arguing is that, similarly, he wanted to assert his autonomy as a visual artist (his freedom from literary critics, “corrupt judges” tarred with the same brush as colonial officials) but, paradoxically, he could only do so by adopting the privileged voice of the writer. His position on the margins of colonial power and local resistance—a position whose instability itself complicates those binaries—helps us to understand the situation of many others who, throughout history, have inhabited the as-yet understudied role of the artist-writer.