Anti-Red Hysteria in American Life

Russian spies held a morbid fascination in the minds of Americans dating back to the Red Scare in 1919, following the Bolshevik Revolution and the creation of the Communist International, of which the Communist Party of the USA became a constituent member, subject to extra-territorial discipline imposed from Moscow.

Global domination was indeed Moscow’s declared aim. The issue, however, was whether this goal was at all practicable.

The Red Scare blended neatly with popular hostility to mass immigration in America, particularly against a surge of Jews fleeing the anti-Semitic heartlands of Eastern Europe. Responding to hostility, many Jews embraced the inclusive internationalist ideals of Communism rather than the outlandish idea of building a Jewish state in the deserts of British-controlled Arab Palestine. But they were a minority, drawn in by radical idealism and anti-fascism. And the American opposition to wider Jewish immigration from these areas was clearly colored by racism, especially the anti-Semitism of the time.

Although there was little justification for the scare-mongering, the hysteria was enough to spur the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which put a halt to the inflow of immigrants without visas. Fears began to dissipate. The 1927 execution of Niccola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italianborn anarchist immigrants accused of murder on doubtful evidence, marked the high tide of the irrational anti-red (and mostly anti-foreigner) hysteria in American life.

Ironically, it was around this time that real dangers actually began to emerge. But, having cried wolf once too often, doomsayers then faced an uphill task through the ’30s trying to convince the government and the American public that Communist threats of any kind actually existed.

Fear of Communism and fear of Soviet espionage were closely entangled because a few members of the miniscule American Communist Party were, in fact, involved in spying for Moscow. Most adherents had no idea this kind of thing was going on—the practice was confined to the shadows, restricted to a few specially chosen for what they had to offer. But, as was the case with Communist Parties elsewhere in the world, those recruited saw it as their duty to serve. And recent archival revelations from Moscow show just how persistent the Kremlin was in its attempts to penetrate the American system.

Initially the civilian branch of Soviet intelligence—OGPU, then NKVD—had little luck recruiting American spies. Yuri Markin (codename Oskar), the illegal “rezident”— as the Russians called their station chiefs—from 1932-34, was murdered by persons unknown, the victim of a violent encounter in a New York bar. His replacement, Boris Bazarov (codenames, Kin, Da Vinci, Nord), worked in tandem with the “legal” rezident (who was under diplomatic cover), Pyotr Guttseit (codename Nikolai). He had much better luck, including recruiting sources with direct access to the State Department and one connected to President Franklin Roosevelt’s inner circle. But the successful spy was recalled to Moscow in 1937, where he became a victim of Stalin’s paranoid purge of those seen as connected to foreigners (mass executions that included even George Kennan’s dentist at the American embassy). His successor, Ishak Akhmerov (codename Yung), took over and married a distant relative of Communist Party chief Earl Browder. Browder himself ensured that ties to Soviet intelligence became indistinguishable from Party work; his wife, Kitty (“Gipsy”) Harris, worked for the Soviets and assisted (and slept with) their British spy Donald Maclean in London and then Paris in the late ’30s.

The most successful operation at that time, however, came from a group of covert operatives organized by the American agriculturalist Harold Ware. The ring included Alger Hiss, Donald, and other federal officials who were convinced that the need to confront the threat from fascism eclipsed all other loyalties. They believed that the road to socialism was inevitable, and that the socialist-leaning policies of Roosevelt’s New Deal were merely the taste of things to come. This operation came under Soviet military intelligence, known as the Fourth Directorate, the NKVD’s main rival. Although their infiltration went deep, none of it added up to much—it was simply “music of the future.”

The stakes were raised, however, when the U.S. entered WWII in December 1941—and the Americans joined the British to develop the atomic bomb. Soviet focus on scientific and industrial intelligence (NTR), which had its own section within the NKVD, switched abruptly from London to Washington. Though intelligence boss Lavrenty Beria dragged his feet on the issue, the NTR foresaw the significant role the bomb would play and pushed it to the forefront of their priorities. Once the directive was set by Stalin in 1942, Soviet efforts knew no limits. Operation Enormoz, directed at uncovering the secret of atomic bomb construction, took high priority. The Kremlin was looking ahead to the aftermath of war. The balance of power could ultimately depend on who had the bomb. And those who volunteered for the cause were putting their lives at risk, as they were soon to find out.

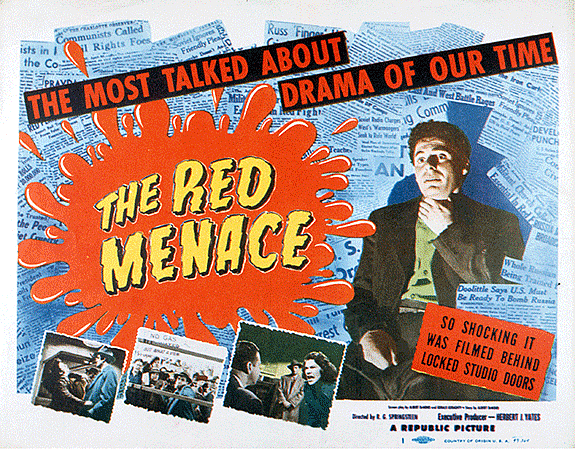

The American authorities had absolutely no idea what the Russians were up to until very late in the game. Good liberals scoffed at the idea that Moscow could be spying on a wartime ally, even as some of their best friends were actually secret members of the Communist Party and spies for Russia. The Roosevelt administration declined to follow up on tips about suspected infiltration. It wasn’t until the very public defection of a Soviet Embassy cipher clerk, who snuck out documentation showing the magnitude of Soviet atomic espionage that had been going on, that the issue finally came to a head. Soviet spy networks were quickly rooted out. The consequences proved cataclysmic for Americans caught serving the Communist cause. Among those swept up were Julius Rosenberg, an engineer who handed Moscow classified information about the U.S. atomic program, and his wife Ethel (against whom there was little solid evidence). By the early 1950s, when the Rosenbergs were executed, Washington was again gripped with widespread hysteria about Communist penetration of American society and government.

The Russians, meanwhile, had been closing down all operations in the late 1940s in order to save their agents; and only well after the death of Stalin in 1953 were they able to begin seriously rebuilding their networks in America. But these networks never acquired the significance they had once had. Atomic espionage in the United States, carried out by misguided idealists who saw in the Soviets a progressive force, proved the high point of Russian intelligence operations targeting America.

Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in 1956, followed by the Soviet intervention in Hungary, destroyed any remaining allure Moscow may have held for young idealists in the West. Thus, although President Lyndon Johnson dearly hoped to uncover Moscow’s clammy hand at work behind the protest movement against the Vietnam War in the 1960s, no amount of effort by the FBI and CIA could uncover anything of significance. International communism, whatever challenges it still posed overseas, no longer posed the threat of creating a fifth column at home.

Though the Russians did have dramatic success in penetrating both the FBI and CIA in the 1980s, it didn’t impact the American psyche as they would have two decades earlier. Yes, they were serious security lapses, but they involved lone, disaffected, or greedy double agents like Aldrich Ames or Robert Hanssen. There was nothing idealistic, nothing connected to a larger Soviet appeal, in their betrayal. By the 1980s, the issue of socialism in American political life had become completely divorced from the issue of relations with the Soviet Union. And as the USSR dissolved from within and came to an end in 1992, the long dark shadow it cast over America finally passed forever.

Even when revelations of post-Soviet Russian spying reemerged in more recent years, most Americans just shrugged their shoulders, or met the news with a nostalgic chuckle and a mention of the good old Cold War days. Other challenges, most prominently 9/11 and Islamic fundamentalist terrorism, had reconnected domestic internal security concerns with international relations in an even more dramatic manner. And as the generations move on, distant memories of grossly exaggerated fears recede from our shared consciousness.